The words of former Provost George Salmon are still infamous in Trinity: “Over my dead body will women enter this college”. It is quite fitting then that the statue of Salmon has him with a slightly peeved look on his face, as 60 per cent of the undergraduates that walk past him every day are now female. Salmon was not the only adversary to admitting women students. In 1892, when a petition demanding the abolition of the 300-year old ban on women students, signed by 10,000 Irish women, was submitted to the Board, they received a refusal including this response:

“If a female had once passed the gate, it would be practically impossible to watch what buildings or what chambers she might enter, or how long she might remain there.”

Women were proclaimed “a danger to the men” and officials in Trinity fought the request for 12 years, with Salmon its chief adversary. Almost immediately after he died in 1904, Trinity College, under Provost Dr Anthony Trail, finally brought in female students and was the first of the historic universities in Britain and Ireland to do so. Despite academic resistance women began to succeed in the university. The first female lecturer was appointed in 1909 and the first professor in 1925. However, they were not eligible for Schols or Fellowship nor were they permitted to dine at Commons in the Dining Hall.

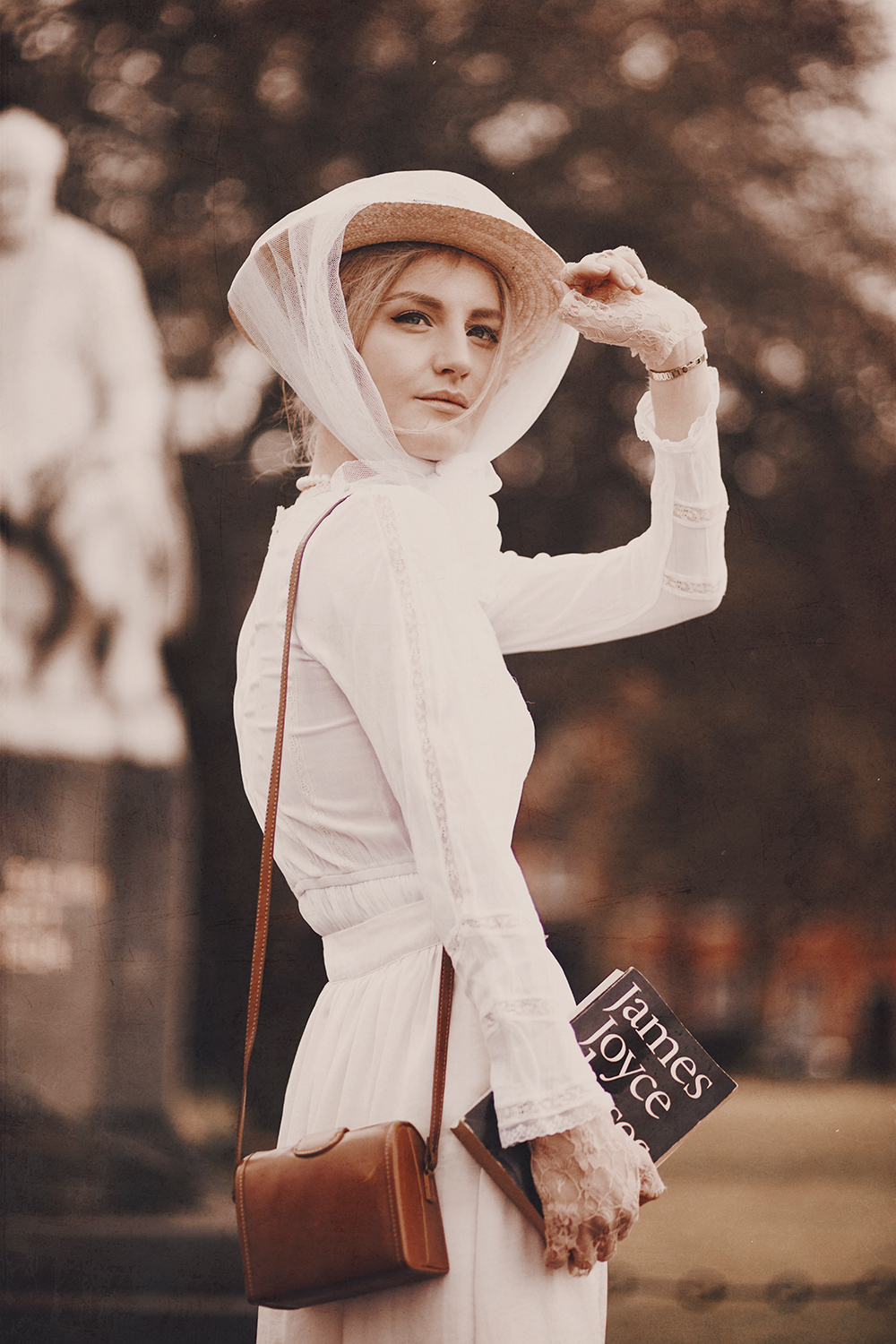

Women were required to wear a cap and gown for fear of being marked absent in classes as “academically naked”. Socially, women faced more ingrained discrimination and were subject to strict rules. They were not allowed to live on campus, so Trinity Hall was founded in 1908 to house the female students. The “Rules for Women Students” required them to a wear cap and gown at all time on campus, for fear of being marked absent in classes as “academically naked”. They were not to visit private rooms without a chaperone and had to leave the College grounds by 6pm, which seriously limited their ability to study or join societies. Women were relegated to separate cloakrooms and dining rooms in House 6 and could not join the major societies such as the University Philosophical Society (the Phil) or the College Historical Society (the Hist). To counter this exclusion, they set up the Elizabethan Society, an all-female debating and social society. The society rooms, in House Six, offered all kinds of services such as “sewing rooms, a telephone, a wireless set, an iron and an ironing board, two sewing machines, and a typewriter”. Stationery was provided for members use also: “a library of novels and books of general interest…papers, women’s magazines, journals and periodicals”. Every year the Elizabethan Society members were treated to a garden party in the fellows’ garden, which was considered “the highlight of the academic year”. It provided a haven where women could socialise freely, free from caps and gowns, and away from the male-dominated atmosphere of Trinity.

For the first few decades, women in their small numbers accepted their inferior position and kept a low profile because they were grateful for their long-sought admission and feared offending the College authorities. Issues like the War of Independence, the Civil War, the Great Depression and World War II all detracted from women’s issues of the day. However as the decades passed and numbers of women swelled, opposition to restrictions on women began to grow.

By the 1950s, the proportion of women was about a third of the 3,000 students attending Trinity and yet they were still restricted to the limited facilities of House Six. The Phil and the Hist still strongly opposed full female membership and it appears the Elizabethan Society had grown apathetic to change. President of 1953/54 Alison Bond said “we had no ambition to join the Phil and the Hist”, and in a 1955 Elizabethan Address, President Eve Ross announced that “a woman’s first duty is to be a woman, otherwise she ought to be a man”.

An opinion piece in Trinity News, written by a woman student contended that “the thought of a world full of women burning with ideas is a sobering one. Life would become too tense and we would all begin suffering as many gastric ulcers as the Americans”.

However, disquiet was beginning to grow among individual female students and it appeared the Graduates Memorial Building (GMB) would become the battleground for women’s equality. In 1963 the Phil welcomed women, not just as spectators, but tradition was broken when President of the Eliz, Rowan Blake-James, was the first woman to speak at a debating society in the GMB. In A Danger to the Men, a book chronicling the history of women in Trinity, Blake-James recalled of the night: “[It was] so memorable in fact that some bright spark decided to fuse all the lights in the building just as I got to my feet to speak.” She was forced to read her speech by candlelight, yet concluded that “an important principle had been established that night that women could debate alongside men”. However, women were not admitted as full members until 1968, and even then, only after the resignation of the conservative president and secretary. The society eventually merged with the Elizabethan Society and as a symbolic gesture, the Phil’s highest-ranking female officer was given the honorary title of Auditrix of the Elizabethan Society.

The Hist proved a more difficult obstacle. Up until 1966 women weren’t even allowed to attend debates as spectators, and in 1963 the Trinity Handbook called it “one of the world’s last masculine strongholds”. Between 1962 and 1968, the issue was debated seven times and repeatedly voted down. An incident in 1961 sparked the rebellion from female students. An invitation was issued to Dr Henry at Sir Patrick Dun’s Hospital to speak at the inaugural of the Hist. This honour was gladly accepted by Henry but when it was revealed in the reply that that the doctor’s first name was actually Mary, a “red-faced Hist Officer hastily dispatched a letter of apology withdrawing the invitation”. This event spurred the first of many “invasions” by women into major Hist events. The following week, eight women hid in rooms in Botany Bay and crept into the Hist Chamber in the GMB. In 1967, Rosemary Rowley, dressed as a man along with with eight other women, invaded a Hist meeting. She was “carried out unceremoniously amid loud cheers”. The invasion with the greatest effect, however, was in 1968 during a major inter-collegiate debate with students competing from Ireland, Scotland, and England. This incident, recorded by David Ford, recounts how the chair on the evening was Conor Cruise O’Brien and it was his daughter, Kate who snuck into the event with a group of women students “in disguise”. During the debate “and with the active support of the Auditor and some of the committee, [the women] jumped up, the meeting dissolved into chaos, and [Kate’s] father supported her”. In the ensuing chaos Censor Joe Revington, who had been “vocal in support”, was expelled. The Auditor was almost impeached (131 to 132 against) and half the committee resigned. Shortly afterwards women were finally accepted as full members. Earlier rhetoric by a Hist member stating that “not until man walks on the moon will a woman set foot in here” proved to be self-defeating, as by the time Neil Armstrong touched down on the moon in 1969, women were finally members.

Other sanctions on women began to be lifted such as the Midnight Ban in 1969. The infamous six o’clock rule had been gradually moved to 7.30 pm, then 11 pm, then 11.30 pm, and in November 1965, to midnight. This meant that women students could stay in the men’s rooms, which was a radical move at the time. A cartoon on the front of the Trinity News at the time depicted a young man carrying a young woman who was throwing her clothes off as they ran into Botany Bay.

Furthering the cause for the women’s movement in the 1970s, Kathy Gilfillan and Cathy de Hartog set up a women’s liberation group, hosting Sunday lunches with a group of women every week to discuss women’s issues. This was at a cost, as Gilfillan recalled in A Danger to Men: “One Sunday a jealous crowd of male students broke down our door and smashed up the bedsitter.” Instead of retreating from their cause however, Gillifan explains that they were “strangely empowered by this”. Gillifan went on to become the Welfare Officer in 1971/72. During this year she produced a contraception guide for students, including information on contraception, information about sexually transmitted disease, and the addresses of abortion agencies in the UK, which was illegal in 1972. The Students Representative Council feared a police raid after the Irish Times printed a piece about it. They avoided prosecution, however, by making the entire student body the authors of the guide, and thus were allowed to distribute it within Trinity but not outside it.

A similar incident occurred again in the academic year 1989/90, when then TCDSU president Ivana Bacik provided the names of abortion clinics in Britain in the Trinity Guidebook. The Society for the Protection of the Unborn Child (SPUC) took the union, alongside University College Dublin Students’ Union (UCDSU) and the Union of Students’ in Ireland (USI) to court and they were threatened with prison. The union representatives were questioned by detectives, told they were under investigation for the crime of “conspiracy to corrupt police morals”, and were subject to extensive media attention throughout the year. In fact, they generated so much publicity that the number of calls to TCDSU from women desperate for information increased hugely, with up to 10 calls a day at times. Mary Robinson, then a senior counsel, originally presented their defence, handing it over to others when she became president of Ireland.

The issue of freedom of information was eventually bypassed by the importance of the X case in the early nineties. The case was finally resolved after seven years and they eventually made legal history before the European Court of Justice (ECJ). Bacik recalled in a Trailblaze speech how difficult those seven years were and how they had prepared themselves for Mountjoy Women’s prison, despite knowing conditions would be tough, and even held a “last night of freedom” party before marching to their trial in the High Court the next day.

As they climb the ranks of academia to the position of professor, the proportion of women shrinks to 14 per cent. Such radical action and bravery in the face of adversity is certainly inspiring to today’s students, and it is clear that the women and men of Trinity have large shoes to fill. Though Trinity has a vibrant feminist community, many submit to the idea that women and men have reached a level playing field and that feminism is no longer necessary. A look at the WiSER (Women in Science and Engineering Research) office’s facts and figures clearly shows a different reality. While women make up 59 per cent of the undergraduate student population, as they climb the ranks of academia to the position of professor, the proportion of women shrinks to 14 per cent. Trinity has a strong glass ceiling when it comes to academia.

Sexism in Trinity’s social sphere is pernicious as well. In 2011 student media reported everything from Law Soc’s playboy party to sexual assaults on the infamous ski trip. In 2012 an all-male fraternity was set up in the college and 2013 saw an accompanying sorority established, reinforcing gender segregation.

Recent figures show a large amount of female students depend on escort websites like Sugar Daddy for financial support and beauty competitions like Miss Trinity are still run by Afterdark. Recent controversies in the Hist exposed endemic sexism. Across societies, particularly in the TCDSU elections, women are highly underrepresented in positions of power. The union took years to adopt a stance on abortion, even when in the 1980s TCDSU leaders were willing to go to jail to support a cause they felt important to women’s rights.

<

Photos by Hayley K Stuart and Erica Coburn for The University Times

Trinity has a long way to go to achieve gender equality, but it has still come very far. DU Gender Equality Society (DUGES) has a strong presence on campus and feminism is alive and well in student discourse, both academic and social. The Hist, once notoriously anti-women, recently established a 40 per cent gender quota for their debates, and Trinity’s WiSER is designated to working toward improving academic inequalities. All of these efforts bring women and men further toward gender equality in Trinity, helping our generation of Trinity women live up to the brave and admirable female students who have gone before us.