When I found out that my interview with David Norris was to take place in his home, I immediately pictured a grand old townhouse in Merrion Square. I was wrong. He lives just off Parnell Street. The house is still has a fairly strong Georgian high-society vibe to it though.

I knocked on the door and that unmistakable voice greeted me through the buzzer, telling me to come in. When I entered the house I noticed a hat stand to my left that looked as if it was about to buckle under the weight of countless boaters, fedoras, and other quaint headgear. Down at the end of the long hall was Senator Norris. He was approaching me with a distracted look on his face, with one finger raised in a “just wait a second please” gesture. He wanted to hear the end of a podcast that he was listening to.

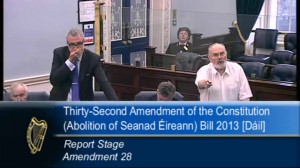

The podcast over, Norris plucked out the earphones and informed me that he was listening to a radio debate about the abolition of the Seanad. This was part of his preparation for the final stages of the referendum campaign, in which he intends to participate vigorously. He revealed that he would take part in as many media debates as possible, adding that he had invited Enda Kenny to debate him on television. This invitation was refused.

He revealed that he would take part in as many media debates as possible, adding that he had invited Enda Kenny to debate him on television. This invitation was refused.

From the moment I entered the house it was clear that I was witnessing a man on a mission. There was one topic and one topic only on David Norris’ mind: the future of the Seanad. Promising that we would get to it eventually, I asked him to talk first about his relationship with Trinity.

Norris is undoubtedly one of Trinity’s favourite sons. He has been consistently re-elected as one of the three university senators. He entered as a student in the sixties and has been linked to the college ever since:

“TCD has been an enormous part of my life because I have been associated it with it in one way or another for about fifty years. I went in with a prize in classics and history. And then I changed and did English, which I loved. The atmosphere was marvellous. But Trinity in those days was quite different. The total number of staff and students was around three thousand. And Archbishop McQuaid had banned Roman Catholics from attending. It was a small, largely protestant university. There were some Catholics who had permission from the archbishop, and some who said ‘to hell with it I’ll go to Trinity if I want to.’ I understand McQuaid’s suspicions though. Because Trinity was always a place for ideas to be challenged, and for questions to be asked. That went against the authoritarianism of people like Pope Pius XII and Archbishop John Charles McQuaid. They felt that if people were allowed to question it might lead all over the place. Because the priest’s word was law and so on. Learning and being educated into a challenging mode was not what they wanted.”

Listening to Norris talk about Trinity is hugely entertaining, if at times confusing.

Listening to Norris talk about Trinity is hugely entertaining, if at times confusing. His enthusiasm makes everything a bit scattered, and he constantly goes off on tangents, forgetting the original point. At one stage he revealed that the Trinity of the sixties was not altogether different. Even then, there seemed to exist a variation of the phenomenon now known as Team England:

“There were some hooray Henrys from England who just hadn’t managed to squeak into Oxbridge. But they were great fun! They had open top sports cars. They gave champagne parties. And they had girlfriends with wonderful names. I remember one that was called Gloria Bolingbroke Kent. Isn’t that marvellous! It was real Bertie Wooster stuff.”

On a more serious note, Norris regrets the changes that have been made to accommodate for the serious financial pressure that Trinity is currently experiencing. He recounted his own experience of being taught in very small groups, with a lot of personal contact:

“The larger numbers have changed the character of the place. It’s great that so many people are getting an education. But the stresses on the system have to be taken into account. In my time, we had small tutorials. When you have fifty or sixty people, that’s useless. There is not enough contact. For us, there were six people in each tutorial. The first week was spent getting to know the group. Then subjects were allocated and everyone wrote an essay. Every week someone would present their essay and that was criticised by the other students under the guidance of the teaching staff. So we really learned. That was real personal contact. And we met in the tutors’ rooms on campus! There were people like Arby D. French, who was one of these great characters who wrote a monograph on P.G. Wodehouse and smoked a pipe. When I said I wanted to write an essay on Joyce he said: ‘Not my sort of thing dear boy so don’t expect an expert comment but if you really feel compelled…’ When somebody asked about heroic couplets he said: ‘Oh just look out the window and you’ll see the mind-set of the Augustan age reflected in the symmetry, balance and harmony. And that is the heroic couplet in stone.’ You can’t get that kind of exchange with fifty or sixty people. There is a general move among universities towards a kind of homogenisation. The one thing I would be afraid of is that the arts and the classics would suffer because of funding issues.”

Norris treasures his relationship with Trinity. He freely admits that if it were not for the well-established liberal tendencies of this university, he would have had no chance of being elected to public office. It was Trinity that educated him, and Trinity that gave him the opportunity to pursue the career that he is currently trying to defend. I could only keep him off the topic of Seanad abolition for so long. Eventually I gave in and opened the floodgates to what was clearly going to be a long and impassioned rant. There was really only one thing on Norris’ mind. And that was the Seanad.

They’re insulting people like me who have worked up to twelve, fourteen, sixteen hours a day in the office!

He appears to be genuinely enraged by the suggestion that the Seanad is fundamentally useless. This has long been the opinion of most of the general public, and it is one of the main arguments of the Yes side in the current referendum campaign. Norris is on a mission to change this conception of the upper house:

“I can’t understand how anybody was able to listen to the kind of things that Enda Kenny and Bruton and the others were saying. That we were useless, that we were a waste of money, and all this. How dare they! They’re insulting people like me who have worked up to twelve, fourteen, sixteen hours a day in the office! I was in the office until midnight the other day even though I’m seriously ill. That’s how I treat my work in the senate. In the senate, instead of defeating a bill, you persuade. And I’ve had at least three or four bills withdrawn. So have other people. Now they weren’t defeated. They were either withdrawn or completely rejigged. And my colleagues can say the same. We are there to persuade. Enda Kenny said that the senate had done nothing to stop the economic crash. Well that’s a good one coming from him. Because I and some other people like myself argued very clearly against the policies of the previous government. The policies of giving in to the banks, of giving in the EU, of not burning the bondholders, of signing the bank guarantee. I opposed every single one… . And what was Enda Kenny doing? He was leading his troops in to support the government. And landing this country in 400 billion of debt!”

One of the more interesting examples that Norris gave in defence of the usefulness of the Seanad was when he spoke about how it can be used to tackle difficult subjects, citing the AIDS debate in the eighties:

“The Dáil were afraid to discuss AIDS in the eighties. So I hired a room in Buswell’s hotel and brought the senate in, and got Fr. Paul Lavelle and Dr. Fiona Mulcahy – a priest and a consultant – to come and answer their questions. And as a result we had an excellent debate. I asked Fr. Lavelle because he dealt with drug addicts in the inner city. And I thought horses for courses. My colleagues would be less likely to accept what I would say. But with a priest who deals with drug addicts and a consultant who deals with AIDS patients, they could ask all their ignorant questions. Which they did. Dreadful things were said! But questions were answered calmly and as a result we had a terrific debate on it.”

Norris did admit the Seanad has become weaker. However, he blamed the political parties for this. The subject of the Seanad is clearly very emotive for Norris. In a similar way to when he spoke about Trinity, it was sometimes difficult to follow his train of thought. However, this time he was fuelled by anger, as opposed to enthusiasm:

“All the political parties have been involved in weakening the senate and using it for themselves… There are about 30 senate bills on the order paper not being moved at the moment. Because they’re trying to stifle the senate. The government is trying to downgrade it as much as they possibly can.”

This leads him on to the accusation that the abolition of the Seanad is a power grab, a move by Enda Kenny to concrete the centralisation of power into an even smaller group. Norris is particularly vocal on this issue:

“I was used to the arrogance of Fianna Fáil. But I have seen nothing like the arrogance of this government. They show a contempt for parliament. The whole government is run by four people. Everything else is a rubber stamp. And that’s very dangerous. Enda Kenny, Michael Noonan, Brendan Howlin and Eamon Gilmore. They basically decide everything. The abolition is a dishonest grab for power. There will be no voice, however weak, to be raised in dissent.”

Currently, it does not look as if the public is in agreement with Norris. He remained hopeful however, saying that the debate would be won in the media, and that it would depend on the arguments made in the last few days. I asked him what it was like to be in the Seanad right now, and what his predictions were in the case of the abolition passing:

“The atmosphere in the senate now is poisonous. There is a lot of suspicions that people are being offered positions. If the abolition passes there will be chaos. The senators who didn’t find their guts before will find them now because they know that they haven’t a hope in hell of getting re-elected. Kenny will have created a big group of disaffected politicians, and I think they’ll take it out on him. I think there could be some degree of political mayhem.”

On the personal implications for him if the Seanad is abolished, Norris is perfectly clear:

“I will be very sad. But I will feel I’ve done my work. I’ll fold up my tent and that’s it. That’s the end of my political career. I have given thirty of forty years of my life one way or another to it. And I have sacrificed my personal life. And to end up being insulted by the likes of Enda Kenny saying I have spent thirty years doing nothing… I just find that unworthy of him and very disappointing.”

I have sacrificed my personal life. And to end up being insulted by the likes of Enda Kenny saying I have spent thirty years doing nothing… I just find that unworthy of him and very disappointing.

This is not the only time in recent years that Norris’ career in the Seanad looked like it might be coming to a close. Not too long ago, it looked very probable that he would be packing his bags to make the move from Leinster House to Áras an Úachtaráin. His presidential bid ended in disaster when it emerged that he wrote a letter on Seanad headed paper pleading for clemency for an ex-boyfriend. However, he is happy to consider what might have been:

“I am an old friend and great admirer of Michael D. I think he is a very good president, but his style is very much academic argument. He makes a very good case. I’m less diplomatic. I might have done some things that you could be impeached for. I would have gone to evictions and stood silently by with the presidential car waiting for me. I think evictions in this country are terrible, especially in light of our history. I would have got in trouble for sticking my nose into things. I think for example it would have been useful to invite some of these distinguished visitors over, and instead of giving them dinner in Áras an Uachtaráin, take them down to Athlone to a soup kitchen. And let them have their soup and look into the eyes of the people they have put out of work.”

Since his failed presidential bid, Norris has been particularly vehement in his criticism of the treatment he received from the media during the election. He now claims to be involved in out of court settlements with various media organisations, but when I press him to name them he does not budge:

“It was the stress from the media situation during the presidential election that caused my cancer. I’m quite sure of it. I have reached out of court settlements of a very satisfactory nature with four newspapers so far. They lied and lied and lied. And now they’re paying and paying and paying. The only newspaper that didn’t blaggard me was the Sunday Independent. As I said, so far I have been successful in four settlements, and I have three more to come. I cannot say who I have settled with because I don’t know if I’m allowed to.”

It seems that now is a very turbulent period in the life of David Norris. On one hand he is busy seeking retribution for wrongs that he feels were done against him in the past, on the other he is trying to protect the future of an organisation that he truly believes in. Although, if you look back over his political career, it has rarely been quiet. Maybe he’s just a turbulent person.

On one hand he is busy seeking retribution for wrongs that he feels were done against him in the past, on the other he is trying to protect the future of an organisation that he truly believes in.

Near the start of the interview Norris told me that he “entered the senate twenty-six years ago in a campaign to end the quiet life there.” Whatever happens on the fourth of October, he can rest assured that he has most definitely achieved that.