Edmund Heaphy | Creative Director

It’s the mind that makes us human. If there is one thing that differentiates us from almost every other species, it’s our mind. And I’m not sure I’ve read or heard anyone who seems to disagree with that. But the very problem with the way we are dealing with mental illness is that we are treating the mind as something which is, in itself, quite separate from the human experience. As if, somehow, mental illness is almost completely caused by some malfunctioning biochemical processes, which are in turn generally just genetically determined and completely separate from our day-to-day lives. The problem with that is not simply that it just seems wrong superficially, but that it also really isn’t supported by the science.

Daniel J. Siegel, a psychiatrist and author of the seminal The Developing Mind, was one of the first to coherently and intelligently point out that this whole “biological determinism” thing doesn’t actually make that much sense. Countless studies have proven that in fact, interactions with the environment, especially our relationships with others, directly affect the brain’s structure and function, and determine how the brain experiences and deals with life. Stressful events, like episodes of maternal deprivation, have powerful and altogether biological effects on the brain’s ability to respond and adapt to future stressful events. But this isn’t news to most people. To the lay person, having an experience of a certain type of event means that you’ll be more prepared in the future for a similar, repeat event — whether it’s grief, work-related stress, or even just giving a speech to a group of people. But it probably hasn’t occurred to you that the reason you’re more prepared the next time is because these experiences are actually physically affecting the parts of your brain that deal with these types of events — so much so that they have powerful neuron-doctrine effects on your ability to cope in the future. Even child-parent attachment patterns, the holy grail of psychology due to Bowlby’s infamous theory, are associated with differing biological and physiological responses, and have also been shown to physically affect the parts of the brain that deal with interpersonal relationships.

The trouble is that we really don’t understand the brain. People talk about the brain and the mind as if they are not one and the same. People talk about nature versus nurture as if there is a lot to be learned from these kind of debates. But we know so little. For instance, the part of the brain that deals with what’s known as executive function, the pre-frontal cortex, is a mystery whether you’re coming from the perspective of neuroscience, psychiatry or psychology. This small patch of brain just above your forehead — referred to as the seat of humanity — controls everything that makes us human. Whether we’re talking about empathy, judgement, insight, moral awareness, ambition, foresight or sense of purpose, it’s all in this tiny patch of brain. And we know very little about it. And the field of neuroscience is quite open about how little we know about it. This is the stuff that makes us special. This is the stuff that makes us human.

The lack of progress in the mental health field stems from the fact that we have all this lark about being pro-psychiatry or anti-psychiatry, seemingly unaware of just where it is that humanity sits. We have the clashing of proponents of talk therapy with the proponents of drug therapy and on top of that, people who disagree about the relationships between nature, nurture, biology and experience. And the list goes on — trust me. We have all these divisions in the field that are, at best, entirely unhelpful, and at worst, altogether ridiculous and unscientific. They completely inhibit clear thinking about one of the most important and complex subjects: the human mind.

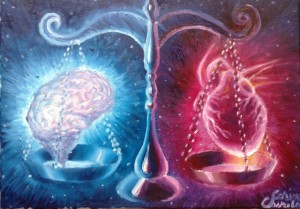

If environmental factors so very clearly have structural and biological effects on the brain, then there is no need to choose between biology and experience. They are one and the same. In that sense, there isn’t much point in trying to distinguish the mind from the brain. It’s all in there somewhere. They too are one and the same. Yet it has become all too common to regard madness and mental illness as medical conditions that are unrelated to our day-to-day experiences, so much so that it’s impossible to think about them in any other way.

If a person’s ability to organise their emotions is a product of earlier structural changes in the brain (themselves a product of earlier interpersonal relationships), then it seems completely illogical to try and treat mental illness without acknowledging that our lives — the environment — in a complex interaction with our genes, have the most powerful effects on our mind’s ability to deal with everything that’s thrown at us. And it’s amazing that this is even controversial. It just makes sense.

There really is no need to choose between the brain and the mind or between biology and experience or, indeed, between nature or nurture. They are all part of the one big, complex process that we call life.

Yet if we simply reduce human experience to the product of genetics and biochemical processes, we veer further and further away from understanding mental illness, and in turn, humanity.