Tom Myatt | Columnist

South Africa’s history was always a turbulent one. Hundreds of years of colonial rule by the Dutch and British Empires fostered huge swathes of emigration from Europe and India in particular, making South Africa one of the most racially diverse lands on the planet. These races have long since viewed each other with suspicion to say the least – but overt hostility and battle was the norm.

This melting pot has resulted in decades of racial conflict, and bowl continues to boil. White South Africans took all political power upon independence from the British, and, despite warnings from the British government who opposed segregation there, the new Republic began establishing the most horrific racialization of all aspects of life seen in any society in history. The country was divided up into districts, each one belonging to a certain race. Simply walking down the street, for blacks at least, was illegal without a permit in other quarters. The government maintained that this was to promote harmony: that the ethnicities could not get along and thus must be kept apart. With this came a promise that each race would see equal economic development and political rights.

This, along with Fascism and Communism, was one of the great lies of the century. And no one outside, and few inside, bought into it. Non-whites, making 85% of the population, often found themselves being treated no better than cattle, and all wealth was monopolized by this white minority.

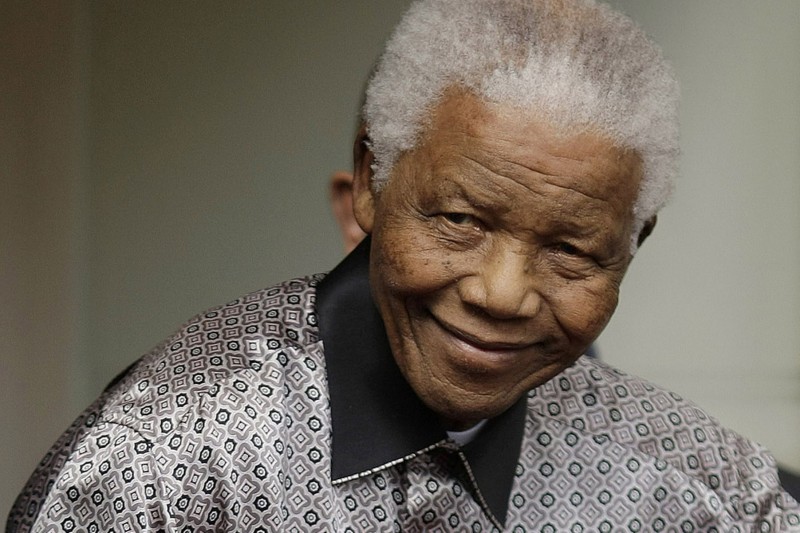

So with not being provided welfare, education, housing, free speech, representation, the ability to even walk through wealthy areas, or often clean water, the ethnic majority began to rebel. At the top level of this insurgence was a young lawyer from the Eastern Cape. In the early 1960s he was convicted for attempted sabotage, terrorism, and high treason, however through decades of internment, he was to become a symbol not only of South African freedom, but also of racial equality across the world. His name was Nelson Mandela.

Without Mandela, it is certain that the struggle equality movement in South Africa before the 1990s would have not found the inspiration and motivation required to peacefully remove their oppressors

I found myself working for a charity in Cape Town two years ago. My assigned suburb, Manenburg, has one of the world’s highest crime rates. One quarter of men have committed violent sexual assault, and two-thirds of the population have been to prison. Young children play with litter blowing past them in the wind on the dirt roads, while gun-strapping teenagers were out searching for their next hit of crack. So being a white kid from middle-class rural England, I was made to know I was not welcome. And why should they be friendly to me?

One evening I went out to a nice dinner in the city centre. The first thing I noticed: everyone in the restaurant possessed light skin. The same was not true of a single waiter. I felt like I was in 1950s America. Being white here is associated with oppression and greed by the rest of the population; the reason for their poverty.

However, the situation would be so much worse had it not been for the actions of Mandela and his huge, dedicated following of racial equality activists, which, it must be remembered, did contain many progressive whites. A family friend of mine in England, who is from Johannesburg, told me of how she was nearly arrested several times by the apartheid authorities, was eventually accused of being a British spy seeking to undermine them, and was deported over to Britain, despite being South African. Yet, being white, the government wasn’t going to put her through the same endeavours that were subjected to Mandela. I saw his cell in Cape Town, and to live in such a small room for 27 years makes Mandela nothing short of saint.

To me, what really gives Mandela a permanent place in my heart is his actions and words following his release. He was a moderate in a very radical party. Many influential elements in their group, the ANC, sought blood: the white man must be subjected and re-oppressed as punishment. Calls for this are still being made by some factions today (see Julius Malema). But Mandela used every single shred of influence he had to say no to his own party. No. To do that would be to simply reverse the problem, and if blacks are to be truly liberated they must liberate themselves from the feeling of resentment. Forgiveness was to be the key, and he was able to do this after the authorities took 27 years of Mandela’s life. He acknowledged not acting upon the desire for reprisal was tough, but in doing so he prevented a civil racial war from occurring in the early 1990s.

Mandela was released from prison in 1990 after 27 years of incarceration. The day will be remembered alongside the moon landing and fall of the Berlin wall. President F. W. De Klerk has largely been forgotten from history, at least outside of South Africa, but he is the man who not only ensured Mandela’s release, but worked with him to carefully dismantle the Apartheid laws one by one. The pair, coming from completely opposed worlds (De Klerk came from a very prestigious political family), were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994 for their efforts in creating a state of racial equality.

The first election in which all races could vote was held in 1994, and Mandela won a landslide. This act alone was a revolution. Black people in South Africa now at least held political power, if not economic. He then continued ensuring all discriminatory legislation was removed from South Africa – and with De Klerk as his vice-president. At the end of the presidential term, in complete contrast to the norm on the rest of the continent, Mandela stepped down and did not run for another term as president. Perhaps he felt he had achieved his goal. Perhaps he knew his reputation had already been made. Whatever the case, his presidency is one of the most memorable in human history, and this man is fully deserving of his place within it. South Africa continues to be a country divided along racial lines, and the lack of Mandela’s influence in his retirement has caused the ANC to begin to fall to the corruption that all parties face after having been in power for so long.

But without Mandela, it is certain that the struggle equality movement in South Africa before the 1990s would have not found the inspiration and motivation required to peacefully remove their oppressors. His death marks the end of an era, and I hope his teaching remain alive within the ruling ANC.