Leanna Byrne | Editor

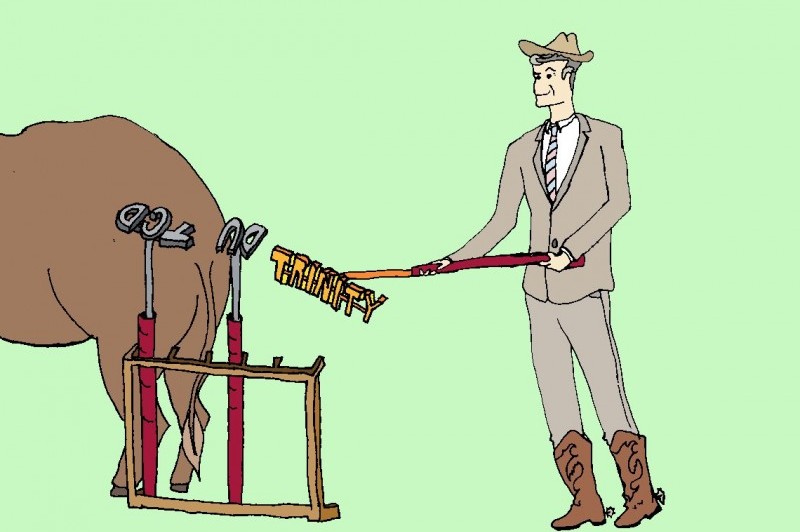

According to his annual review, our Provost Patrick Prendergast finds himself in the midst of a period of transition in higher level education. In order to keep up with the rest of the leading universities, Trinity needs to meet the expectations of the “global generation” by attracting new industry and becoming more innovative. All of this sounds very attractive, which is probably the point. At the same time, what happens when a college is not just implementing change, but marketing the change as well? Does the narrative support the actions or is it the driving force in itself?

My interview with the Provost took place in his library shortly before he turned on the lights of the Christmas tree in Front Square. I was instructed to ask him questions about the Trinity Global Graduate Forum (TGGF), the identity initiative and the exciting stuff about innovation and entrepreneurship that Richard Bruton has been grinning about recently. Bearing in mind that the consultation process for the five year strategic plan is set to begin in the next few weeks, these instructions gave me enough scope to ask about the rumours of privatisation and growth plans that everyone has been talking about.

The TGGF was hosted last month to connect with over 100 of the best and brightest Trinity alumni globally. The forum was broken down into five breakout sessions: education, growth, funding, technology and our reputation. I tried to steer the conversation to combine the topics of funding and privatisation, and was met with a firm response.

“Everyone is free to have that conversation – we have academic freedom after all. So I wasn’t surprised that privatisation came onto the agenda”

“Clearly when you have alumni from around the world coming here, many who are working in North America for example, where you have a mix of private and public universities, and even the public universities would have substantially more private funding in the US, clearly the conversation was going to come onto the agenda. Everyone is free to have that conversation – we have academic freedom after all. So I wasn’t surprised that privatisation came onto the agenda.”

Without giving his personal preference, he went on to tell me that the privatisation of Trinity is not something that fits easily with the current Universities Act (1997) that redefined Trinity as a public university.

“That’s only something that can be changed by legislation,” he explained. “So I don’t think it’s realistic to talk about straightforward privatisation in the way that it was done.”

Yes, but is privatisation even feasible? He responded by reminding me of the Act he had just spoken about. I proposed this hypothetical situation where there was no Act. Did we have enough in the coffers to sustain ourselves if other private universities receive up to 30 per cent of their income from alumni funding, whereas we’re stuck at a measly 3 per cent?

He informed me that I needed to be clear about the fact that Trinity has spent most of its life as a private university. The college was founded in 1592 as a chartered corporation. It was a royal charter in receipt of government funds for activities, but not subject to regulations as part of the public sector. Of course, all that’s changed now with the Universities Act. However, I suggested that it wasn’t feasible because of funding, I was wrong about that – funding isn’t the crux of the matter.

“I think the crux of the matter is really legislative,” he said. “The government and the Universities Act that makes Trinity a public university. I think we can achieve most of these objectives as a public university if we can find a way to operate with the constraints we are under.”

What are those constraints? “I think a key aspect is how we can spend the money that we get.

What are those constraints? “I think a key aspect is how we can spend the money that we get. We raise private money and we are to be as flexible as possible in how we spend that money. One thing that is a constraint is the employment control framework is in keeping with government regulation that constrains us and we do that because we are a public sector university.”

So it’s the government and legislation that are putting the universities under pressure? No, it’s because of the funding environment. Although he admitted that things are made more difficult by the management of these resources which is not fully in control of the university. The strain also comes from various government regulations like the employment control framework or… well, that one in particular.

Provost Patrick Prendergast and Minister for Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation, Richard Bruton TD at the launch of Trinity’s new innovation strategy. Photo: TCD Communications.

Since we were on the subject of funding, I asked if it was important that we prioritise international students to generate more revenue: “I don’t think international students should be brought in solely as a revenue generator,” he explained. “Although we do get a higher fee from international students, there are other ways to generate revenue.”

On the matter of international students, increasing numbers of non-EU students is good for a cosmopolitan global education that Trinity has to offer. This is the primary reason. Universities that use international students solely as revenue generators, well, he didn’t think that was a successful strategy. Trinity can be better than that.

Surely, then, if becoming more international is the priority, this is why we’re undertaking the “identity initiative”? Wrong again. Well, not as the primary purpose. It’s really about student improvement. Even I would see the benefit from graduating with a degree from a university that is well recognised around around the world. In fact, it would be valuable for all of Ireland to have a university that’s name is recognised around the world.

I suggested that Trinity College was well known enough, but the Provost disagreed saying that he didn’t think it is recognised around the world as much as it could be. “There are some universities that everyone knows,” he said. “Then there are some that are only known locally. It’s reasonably well known in the English speaking countries… It can be better known.”

Is rebranding Trinity the most important step in making this well-known, global university? Aren’t there more important things to concentrate on?

Fair enough. But is rebranding Trinity the most important step in making this well-known, global university? Aren’t there more important things to concentrate on?

“Well,” he said. “You can do a lot of great things, but unless you tell people, they are not going to be widely known. We have been doing a lot of great things and we’re going to be doing a lot more great things.” With the identity initiative Trinity are striving to ensure the quality that they offer in education and research is more widely known. He reminded me that this is an important benefit not just for students and staff, but the country as a whole.

Having recently completed the questionnaire he emailed to all students relating to Trinity’s identity, I asked him how he would answer the question relating to what he thought Trinity’s identity is. This caused a bit of confusion. After all, what we answer in the questionnaire is confidential. Anyway, he didn’t remember.

I told him that I wasn’t necessarily asking for his survey answers, but if he would like to answer my question…

What he thought the Trinity identity is?

Yes. What is the image we want to portray to the outside?

The Provost believed his opinion on the matter was uninteresting; however, he expected the survey to say that Trinity is independent, with an international standing and an outstanding class of students.

Now, I asked, what did he make of the reports that the rebranding would drop the “College Dublin” from Trinity. I had read it in one of the many interviews he’s given. At this, the newly appointed Director of Marketing and Communications, Bernard Mallee, intervened and said that “Trinity” would remain, but a particular variation of it would come from the consultation process. Prendergast replied by saying that “Trinity will always be Trinity”.

What about the “College Dublin”? Is it important for Trinity to be in Dublin? “Trinity is also the University of Dublin. Everybody in the country knows that.”

I remarked about the clubs and societies using “DU”. Exactly, it’s important for Trinity to be understood to be the University of Dublin, but it’s confusing having two names.

“For many people abroad, a college is a secondary school, not a university. So, if you go to get a job in Hong Kong and you went to Trinity College they’ll say: ah she didn’t go to a university then. That’s not helping you. We have a requirement that we address this issue.”

I asked him if he would call it Trinity University Dublin (TUD). He told me that he didn’t think that particularly the best. There are many options. Again, it all depends on the survey. He certainly isn’t going into the process with any preconceived notions about what might be the best way.

But does the college even want this identity initiative? Well, he said, looking for clarification, who’s the college? I began listing groups off the top of my head: the staff, the fellows, the students…

“All those groups?”

“The academics, societies, capitated bodies… I’m sure I’m leaving somebody out.”

“So as far as the Board represents the College then yes the College does want us to look at it.”

He told me that he obviously doesn’t know. He can’t ask everyone. Perhaps I was being unfair, but I was sure that at least somebody mentioned it. He informed me that they hadn’t.

“The Board of the College want it and the Board of the College contains elected representatives of faculty and staff and students,” he said. “They approved a communications strategy that included the Trinity identity initiative. We’re following through on that Board approved strategy. So as far as the Board represents the College then yes the College does want us to look at it.” He further reassured me that any outcomes will be put to the board, so nothing is going to happen that doesn’t have the buy in of the college community. Mallee repeated “it’s in the strategic plan”.

The Provost turned to me again and continued by saying: “If you ask me out straight, I haven’t asked the capitated bodies, I haven’t asked them all if they want it or not, but I believe they do. I am happy to see this work being carried out. There are some vocal opponents to it, but I believe the majority, be it staff or students, understand the value of a close look at Trinity’s identity and if we have developed it in a way that is to everyone’s advantage or not.”

The thing is, I’ve learned that the best way to think of Trinity is that it is made up of dozens and dozens of autonomous pockets, who enjoy residing under the Trinity umbrella as long as they are granted the liberty to do as they please. Asking them to implement changes and to change their outlook in order to become globally orientated is one thing, but to suggest that means they will all be united in their mission and vision ignores the true identity of Trinity: blissful fragmentation.

I told the Provost this by saying that after being here for almost five years I felt like the university was like “the Republic of Trinity” with so many different parts to the whole. Surely, then, it would be very complicated trying to make us all conform to one identity and name?

He paused for a few seconds. “Well, we’ll see won’t we? We’ll just have to find out.”

Illustration by Stephen Lehane