Daniel O’Brien | Senior Editor

Discussions about money in sports frequently target spending on and by top athletes. Stories about Premier League footballers frame wages in terms of weekly earnings, as if to emphasise the fact that these people make more in a week than many fans will in half a decade. Meanwhile, the money that actually drives the sport goes largely unquestioned. As much as this culture feeds into the spectacle and mystique of the game, it seems a bizarrely unfair practice that is standard behaviour in exactly zero other industries around the world.

The problems start when we think of professional sports as anything other than a typical business arrangement.

The problems start when we think of professional sports as anything other than a typical business arrangement. If someone came into your workplace, off the street, and observed you for a few hours once a week before declaring to the world that you are grossly overpaid, you would rightly tell them to get lost. They would be far removed from knowing the full context of your employment, and even if they somehow did it would hardly be their place to comment on it. Broadly speaking, people are justified in earning whatever their employer is willing to pay them. The wisdom of that agreement can only be commented on in the context of the economic return generated by the worker. The fact that someone earns “a lot” of money clearly doesn’t reflect anything about whether they are over- or underpaid.

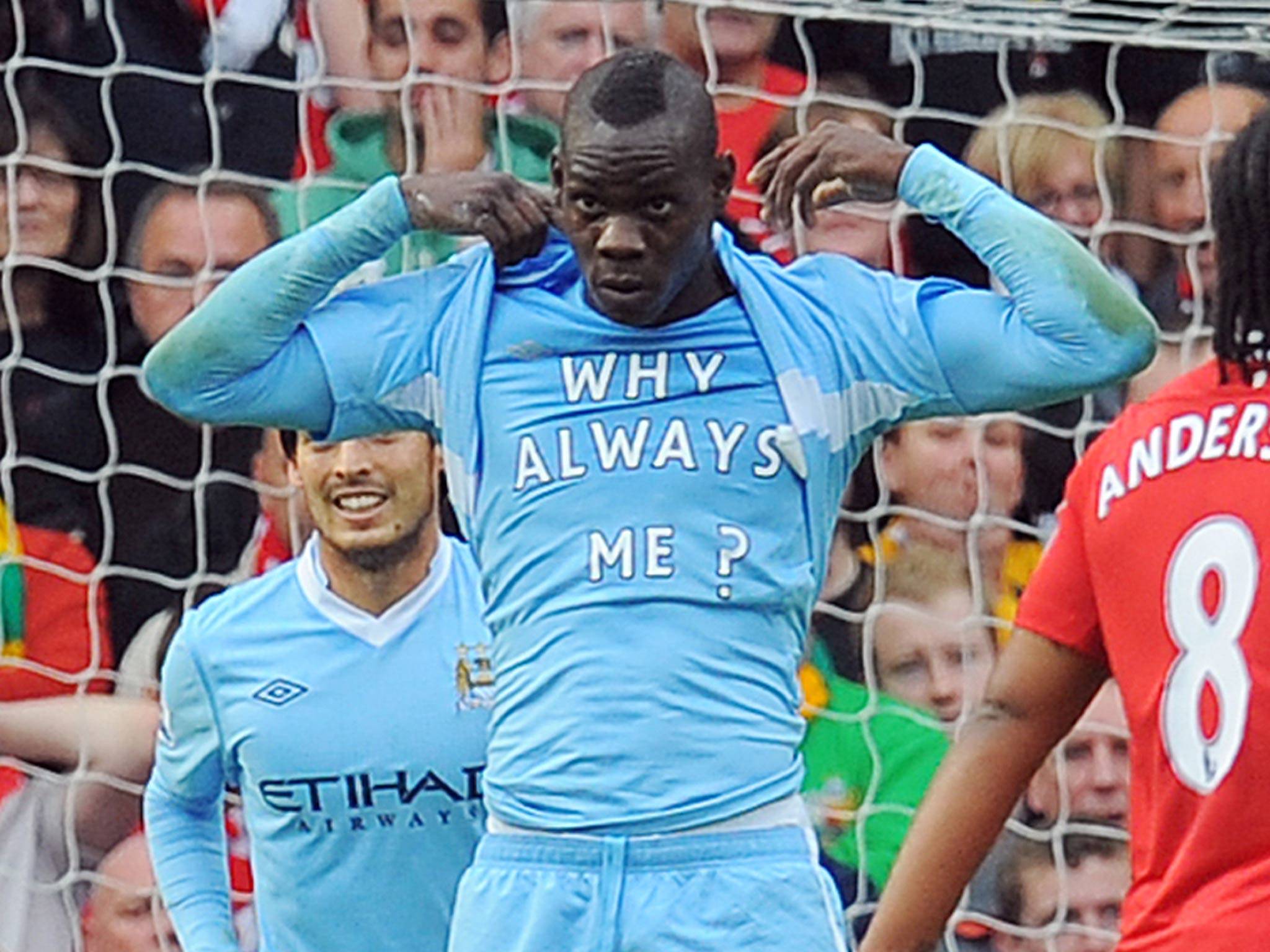

Why, then, is it fair to comment on and criticise the finances of athletes? The first and most obvious answer seems to relate to the type of consumption associated with sports figures, i.e. conspicuous and ostentatious. NFL running back Marshawn Lynch once famously put up velvet ropes to block off his white Lamborghini when he parked it on the street (see also: everything Mario Balotelli has ever done). The types of money we imagine being thrown around in nightclubs for fun could feed a family for months. Yet the real money lies in the owners box. As the famous saying goes, the people on the field may be rich, but only the guy who owns the field is wealthy.

That important distinction carries a number of complicated issues within it, with class stigmas being perhaps the most prominent. Owners have already made their millions, often through less than reputable business ventures (oil barons, dodgy real estate, etc.). They are essentially earning more money because they have a lot of it already. I’m not saying that is unjustified, but we don’t think about that money too often, because watching sports is all about those still earning it through labour on the pitch. We see owners as having justifiably “earned” their wealth, simply by virtue of the fact that it exists, while athletes must strive every day to again prove themselves worthy of their income. We judge athletes for the ridiculous things they buy and do, ignoring the blatant reality that some people have enough money to casually spend many millions of it buying and selling sports teams. The consumption may be less obvious, but it is no less ridiculous.

We see owners as having justifiably “earned” their wealth, simply by virtue of the fact that it exists, while athletes must strive every day to again prove themselves worthy of their income.

The truly wealthy individuals in sports benefit from the public’s obsession with athletes’ earnings. Most American leagues have some type of salary cap limiting the total payroll of any one team. That cap, instituted collectively by team owners, can rise every few years through collective bargaining agreements, but the players inarguably earn less than they could in an open market. The public treats any attempt by the players to rebalance proportional revenue distribution as pure, malignant greed. Meanwhile, within the salary cap framework, individual players are criticised by fans and media for taking the full – and already undervalued – compensation to which they are entitled, if doing so in any way undermines the team’s success.

When the financial interests of an individual are perceived to be limiting the organisation, it somehow becomes the less wealthy person’s obligation to take even less money. Ownership is rarely asked to take a hit; only in the most extreme cases (Arsenal, Florida Marlins, etc.) do fans direct anger at stingy owners rather than those on the field. And even when that does happen, it is more often framed as an organisational failure than personal greed or misconduct. The NBA, for example, institutes a salary “floor”, legislatively preventing teams from spending below a certain amount on players’ salaries. They have to do so because, otherwise, bad teams looking to tank and get a good draft pick would not hesitate to spend as little as possible on truly awful players. They could, rightly or wrongly, frame that stinginess as a path to future success, but we would never accept such an excuse from an athlete getting paid but not playing.

When the financial interests of an individual are perceived to be limiting the organisation, it somehow becomes the less wealthy person’s obligation to take even less money.

It is understandable for fans to argue their right to criticise players’ earnings based on some of level of “stake” that they hold in the team’s success. But it is equally worth recognising that most of the athletes that bring so much entertainment to billions of people around the world are objectively underpaid. When complaining about your team’s lack of success, or the general culture of money in sports, first consider what is being done – or could be done – by those with the true power and wealth.