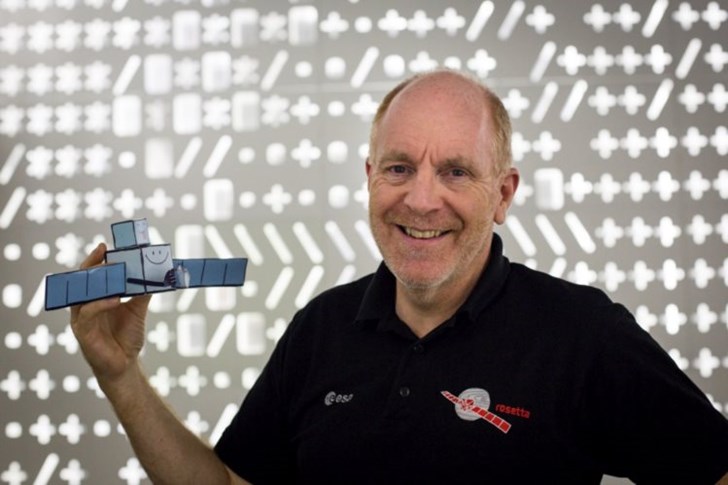

As part of Space Week, Prof Mark McCaughrean, the Senior Science Advisor in the Directorate of Science at the European Space Agency (ESA), spoke in Trinity last night about the Rosetta space mission. The mission came to a dramatic conclusion last week when the Rosetta probe crash-landed on its target comet, having travelled more than 6 billion kilometres in space over the last 12 years.

After a slow start and a last-minute venue change due to technical difficulties his talk, “To Catch a Comet”, began with a discussion of why space travel is so imperative for humans. Comets, along with other kinds of astronomic material, provide scientists with a unique opportunity to study materials leftover from the formation of the solar system. And this matters because it is thought that by exploring space we may find clues as to the origin of many of the organic materials found here on Earth.

McCaughrean discussed why the ESA first decided to try and catch a comet. A comet is normally defined as a ball of ice and rock with a tail of plasma and fragments of itself trailing behind it and are somewhat of a rarity in the Northern Hemisphere. The first encounter between a space probe occurred in 1986 when Halley’s comet crossed the path of the Giotto at a speed of 68 kilometres per second. From this brief encounter a lot of valuable scientific insight was gathered, including the first picture of the nucleus of a comet. From then it was decided that further exploration of comets would be something worthwhile to pursue.

This effort came about in the shape of Rosetta, a space probe weighing three tonnes and equipped a variety of cameras, drills and other scientific equipment designed to measure a variety of parameters. Attached to Rosetta was a smaller module, Philae, that would be launched onto the comet to collect surface data.

According to McCaughrean, the original target of Rosetta was a comet known as 46P/Wirtanen, which fell through because one of the rockets that was to be used to launch Rosetta exploded. This meant that by the time a new rocket had be acquired 46P would have passed by. Instead of 46P they turned their attention to 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, discovered by Soviet astronomers in the 1960s.

Rosetta finally launched in 2004, much to the delight of everyone at the ESA. After 10 years the comet and Rosetta finally crossed paths, with Rosetta entering actual orbit with the comet. McCaughrean spoke of the tension and anticipation felt in the room as Rosetta and 67P rendezvoused. Later in 2014, Philae was released in a manner described by McCaughrean as being similar to throwing a dart at a dart board while blindfolded. Unfortunately, 67P’s surface crust was much harder than anticipated owing to the sun’s drying effect, and Philae ended up bouncing along it’s surface for two hours until it finally came to a stop beneath a cliff-like overhang. They were fortunate in that Philae did not bounce higher than 90 centimetres per second – had it done so it would have been liable to fall off the comet, wasting years of hard work.

The comet on which Philae landed was four kilometres in length and appeared to be made up of two comets that had collided at some point. The surface, which they thought would be smooth, was in fact largely variegated and riddled with cliff-like structures and pits arising from escaping gases and heat from the sun.

Philae provided data from the surface for three days, and then once it had recharged, for another three days. They found many organic compounds including phosphorus and glycine to be present on 67P. Based on their findings it seems that at most one per cent of Earth’s water comes from comets like 67P, still leaving many of the scientist’s original questions unanswered.

In an attempt to capture images that would provide invaluable insight into the comet and considering Rosetta had fulfilled the goal of landing Philae on the comet, it was decided to crash Rosetta into 67P. Thus, at exactly At 11.19am on September 30th 2016, Rosetta crash-landed on the comet.

In the final emotional words of the night, McCaughrean spoke of what an achievement it was to have carried out a successful mission, saying that humans are “remarkable little beasts, look at what we did with a 4.6-billion-year-old object barrelling through the solar system”.

Despite Rosetta’s mission being complete, the ESA continue their work. McCaughrean finished with words of encouragement for those engaged in pursuits that capture their hearts: “Even the greatest of journeys must come to an end, but important is to realise your ambitions to see and do wondrous things, and to light a path for those who follow after.”