Trinity’s archives are home to over 20,000 collections, with materials dating from the 13th century to the present day. Speaking to The University Times, Jane Maxwell, one of the archive’s gatekeepers, explains that her interest in material history began when she was an undergraduate student: “During my undergraduate years studying history, I worked for two summers in the National Archives as a student assistant and I was instantly smitten, and resolved to take a postgraduate archival training course.”

Maxwell’s main area of focus is the acquisition and research of material relating to the lives of women in the 18th century. She recently finished a PhD that looked at the domestic letter as a source for women’s history. At a time when letter-writing culture is diminishing, the subject of Maxwell’s PhD is particularly interesting.

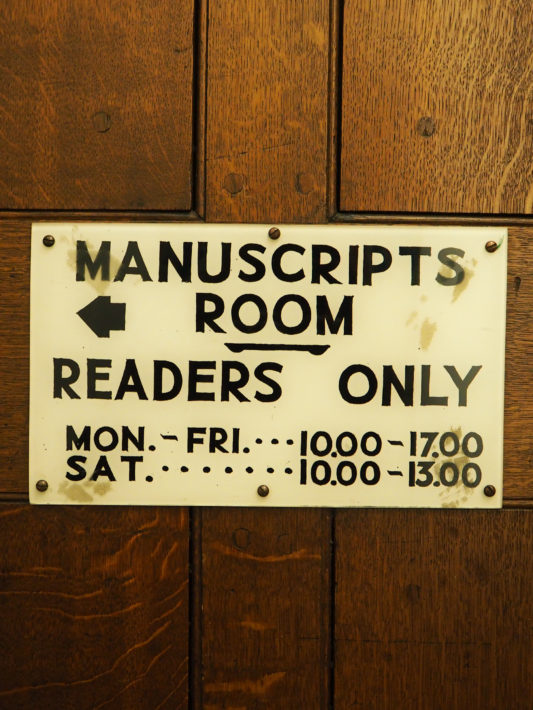

As I sit in the manuscripts and archives reading room, among the stacks of boxes crammed full of letters, I wonder what effect this decline of letter writing will have on future research. “You can only assume that researchers will be as inventive in the future as they are now”, Maxwell says. “I’m quite confident that regardless of what happens, researchers will always respond creatively and work around the gaps.”

We speak about the cause for such gaps. In the past, strands of research were very predictable, and thus archival material was mostly composed of official records. When researchers began to diverge from these predictable strands, huge gaps became evident. “A lot of women don’t appear for hundreds of years and children are completely invisible”, Maxwell explains. Fortunately, historians are used to working around silences. “It’s very creative and it’s reflective of the human condition because obviously what you don’t say can be as important as what you do say”, she explains.

I’m quite confident that regardless of what happens, researchers will always respond creatively and work around the gaps

In the acquisition of material the archivist has a responsibility in ensuring that there are as few silences as possible. For Maxwell, these gaps usually relate to the domestic lives of women and children. Acquiring the materials of Irish poet and novelist Leland Bardwell was particularly important: “The reason I liked it was because it was very symbolic of how women’s archives fall through the cracks.”

She explains that many libraries are in competition for the same literary material, but in the case of artists like Bardwell, work often gets lost. “She has never really been a huge name, nonetheless she worked a full life. She was really supportive to lots of artists. I think anyone who was trying to make it in the 60s, as a writer or and actor say, slept on her couch.” She adds: “That kind of thing, where you are important at a personal level but you never win the Nobel prize, you could easily see how she could slip over the edge. So I have to say I was very pleased to be part of bringing that in.”

Maxwell highlights Trinity’s collection of Beckett’s materials, an asset that is a matter of great pride for the library. While the collection includes material of immense “literary importance”, notably the manuscript of Beckett’s short prose text from the 1960s, Imagination Dead Imagine, Maxwell is drawn towards material in the collection that could hook anyone’s imagination.

She mentions two of the earliest Beckett materials in the collection. One is a small undergraduate essay that, to Maxwell’s delight, is littered with spelling mistakes. The other is a little sports day program in which Beckett and his brother are listed as participants in a boxing tournament. Maxwell explains: “He was in a school on Harcourt St which was all very manly, you know, ‘let’s teach the boys to box’ sort of a thing.”

Maxwell approaches Beckett’s materials in a refreshing way – she refuses to conform to the elitism so often found in Beckett scholarship. “Studying Beckett can be a bit overwhelming”, she says. “If you just say, ‘well, here his spellings are bad and here he is as a nine-year-old in a boxing ring’, it gives an insight into the ordinary development of somebody who eventually became a great artist.”

It’s the young people that are coming to it, and because they didn’t all meet him and think he was God, they are coming to him as open minded as they do to everything

Biographers tend to give Beckett a sort of godlike status, which can stagnate conversations relating to collaboration in his writing. Maxwell recognises this and offers an alternative way to engage with the material. “You know, he was just a kid. Here his spellings were bad, and here he is as a nine-year-old boxer. It can give you a different perspective.” She continues: “It’s the young people that are coming to it, and because they didn’t all meet him and think he was God, they are coming to him as open minded as they do to everything.” This change of approach is beginning to address silences in Beckett scholarship, most notably the writing of women in Beckett’s life and his refusal to accept the possibility of their influence in his writing.

Trinity’s manuscripts room houses a trove of delights.

Maxwell recently made a discovery that adds to this conversation about collaboration. She recognised the handwriting of translator and critic Barbara Bray, with whom Beckett was intimately involved from the 1960s right through to the end of the 1980s. “Beckett’s handwriting is terrible but because I am able to read it, I am often assigned Beckett material.” Maxwell says that she approached this material as an archivist, not a scholar. “I look at it with the same scrutiny that I would look at any other archival work. Beckett scholars can sometimes see what they want to see.”

Maxwell noticed tiny little notes in the margins of the author’s work. “I was looking at it and I thought, ‘hang on, he wouldn’t say that to himself’.” She explains: “What’s written on it is not ground-breaking. It’s not anything like ‘Sam, I think Godot should arrive’ – it’s nothing like that. It’s minor details but that fact that it’s there, that is more important.” It encourages a much-needed change in the approach to Beckett research.

Maxwell praises the enthusiasm with which undergraduates have been using the material in the archives. “No library like this ever stops collecting material, and we are not collecting it in a vacuum. We are collecting it for use, all of the time. It is absolutely delightful for us to see changed usages.”

She mentions a recent discussion she had with a performance artist who requested to view materials to form the basis of a new performance piece. Maxwell is encouraged by this innovation and is excited by the prospect of this change in research approaches. “If you come in and say, ‘I want to do modern dance on your archives’, we will say ‘yes of course, but could it be beside?’ It’s wonderful. If you don’t change, you die. We are definitely changing. We want more of that.”