It’s 9:46pm on March 22nd, 2021, when my phone buzzes with a text from an old friend back in Colorado. “Not sure if you’re awake but there is an active shooter at the King Soopers on Table Mesa in Boulder.”

I know that grocery store. My dad would take me there after work. He would peruse the shelves, knowing each aisle by memory, his shopping lists regimented unless another item was cheaper and his spontaneity would be allowed once he checked the nutrition facts.

My father has a routine down to the clockwork of his IronMan digital watch. Even though it’s been three years since I’ve lived at home in Boulder, I still know that on Monday afternoon he will have a meeting and then go shopping at the neighbourhood grocery store. I do the math to tell the time difference. It’s 2:46pm in Colorado.

At first I hesitated to call him and try to warn him, fearing I was being paranoid. But then I reminded myself that I’m an American citizen and this has happened in a movie theatre, multiple high schools, a Walmart, a middle school, a Planned Parenthood clinic and a random residential street. All in my state – all in my lifetime. I dial the long-distance number, hoping I’m not too late. In the time it takes to ring, while mutely terrified, there is a feeling of finality – that this is what we trained for.

My dad is safe and alive. But ten people were shot and killed with a Ruger AR-556 while buying groceries that day. Dad was spared, but not because the gun was outlawed: the alleged shooter Ahmad Al Aliwi Al-Issa bought his semi-automatic rifle legally, six days before the shooting.

Background checks didn’t protect Dad: Al-Issa passed Colorado’s universal background check with flying colours, despite being previously convicted of third-degree assault. Dad wasn’t protected by a county judge who, four days before Al-Issa bought the gun, blocked a Boulder city ban on assault rifles after a suit from the National Rifle Association (NRA). He wouldn’t have even been saved by that ban because the shooter bought his gun a 30-minute drive away in the city of Aurora.

No, Bill Stalhuth was saved by a mould problem.

I am 21 years old and have lived through well over 100 mass shootings in my home country. Throughout my public school experience, we were primed to expect a gunman

On every Monday but this one, my father has a meeting at the Starbucks in the King Soopers from 1:30 to 2:30pm and would then go inside to pick prescriptions for his client and buy groceries. The gunman opened fire at 2:30pm. Because his client’s house had a mould infestation, he decided to cancel the meeting and did his errands at the store an hour and a half before the shooting.

I do not have the US government to thank for saving my father. I have a well-timed mould infestation.

I am 21 years old and have lived through well over 100 mass shootings in my home country. Throughout my public school experience, we were primed to expect a gunman. I’m from Colorado, home of the American school shootings’ original sin: the Columbine High School Massacre of 1999. We were told the story as a cautionary tale: two students, bullied and outcast, come to school one day and kill 12 students, one teacher and themselves. The moral was an anti-bullying programme, with the not-so-subtle message to children that the killers came from the inside. I was angry, upset and terrified when the King Soopers shooting took place in my hometown. I was not wholly surprised after the shock. And neither were the members of my family and community.

James Bentz was in the meat section when he heard the shots. “It seemed like all of us had imagined we’d be in a situation like this at some point in our lives”, he told the Denver Post. Perhaps what I find most disturbing in these conversations is the collective hopelessness we have about ever solving or stopping this issue. I only fully grasped this when I left it for Ireland.

Much has been said about America’s gun culture that has made the second amendment to the US constitution – the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed – to be valued more than the lives infringed by gun violence, death and trauma. This culture, mythologising guns, making them national heritage, right and duty, is key to understanding the epidemic of these shootings and what allows them to continue.

However, what I think needs to be explored alongside gun culture is the truly devastating impact of mass shootings on the communities in which they take place. Through repeated mass shootings in public spaces, and no legislative action that has successfully prevented them over the past three decades, American citizens have been forced to normalise this violence or face a life of paralysing anxiety. In my own experience, and talking to other Boulder residents, the perspective on the mortality racking thought of shootings is overwhelming, but due to their frequency, mundane at this point. We resort to dark humour, thinking about exit strategies in public buildings without feeling the full fear of risking our lives, mourn the dead and then move on.

At the Boulder King Soopers shooting, two teenage girls hid in a closet after witnessing people being shot. They were well trained by the lockdown drills we all did in school. We were told to hide in closets if there were any in classrooms – the more wood between us and the bullets, the better. Twice a year we would have lockdown drills alongside our routine natural-disaster drills, implying that an assault rifle is only as unnatural as a tornado.

Huddled in corners of a darkened room, hidden from papered-over windows, we’d joke that someone should make a Soundcloud beat to the tune of our probable deaths. During one drill, the school police officer knocked on the door and asked if everything was alright, could we let him in? Well trained to expect such an appeal, we ignored him and kept silent in the shadows. That’s what a murderer would say. He jiggled the handle and, to our alarm, opened the door. The white light of the hallway poured a halo around the officer’s flabbergasted face and into our gaping mouths. “It’s a lockdown, ma’am … You need to lock the door.” Later we’d joke that maybe ditching Ms Smith’s class could be a quite literal lifesaver.

Mass shooting culture is the production of inevitability. It is making the continual fear and facing of one’s mortality into an idea to be grappled with, laughed at, instead of an emotion to be felt.

During one school shooting drill I remember asking my friends: what if the shooter is a student? If, like Columbine, the shooter knows the procedures we’re currently practicing and can circumvent our protective measures?

But Boulderites aren’t unfeeling. Americans aren’t immune to the violence. For everyone I spoke to, the first precedent shooting at Columbine High School in Aurora, Colorado in 1999 was a landmark, core memory analogous to 9/11. My mom remembers calling my dad as it happened, the kind of call where two people can only comfort each other by asking questions with no answers. How could this have happened? How is this possible? It was unexpected. They didn’t yet have the script we have now.

My cousin Maddie Davis, who was six when Columbine happened, remembers being picked up from school and everything shutting down. She turned on the TV and every channel was reporting on the shooting.

“They started putting up the pictures of people who were confirmed dead and I will never forget, it was that Sarah McGlochlan song ‘I Will Remember You’ that they had playing as people who died photos were flashing up on the screen. I will never be able to hear that fucking song without thinking about Columbine.”

She was too young to fully comprehend it but remembers being scared, confused and truly sad that something horrible happened. Born in 2000, I’m part of the generation that has never known American life pre-Columbine. It loomed in the background, coming up in school anti-bullying programs and the dark corners we hid in during lockdown drills. During one such drill I remember asking my friends as we got up from our cramped positions: what if the shooter is a student? If, like Columbine, the shooter knows the procedures we’re currently practicing and can circumvent our protective measures?

No one had an answer. We moved on.

Some parents tell their kids about shootings and others want them to be innocent about it as long as they can

Two weeks after the shooting, I called my fifth-grade teacher Monica Boykoff. I was wondering how it was to train young children like me in those drills. She says she has mixed feelings about the drills that have become a normal part of her teaching career. “When I’m sitting there in the dark with the kids trying to keep them quiet, we try to normalise it for them so they’re not panicky, but you can’t help but sit there thinking, like, the reason why we’re doing this, what could be happening.”

However, she describes needing to put that in the back of her mind to continue doing her job. “I wouldn’t say it’s something that we think about regularly. When we have drills, we go into the teachers lounge to sort of lament … you just go about your life.”

She says she has less fear that a student will come to their school as a shooter because it’s an elementary school – she knows high school teachers might have more legitimate, precedented anxiety. Nonetheless, she sometimes has a student who she can tell feels anger towards her. “I think to myself: God, are they going to come back and shoot me someday?”

She and other teachers note when parents get upset with their children’s grade or a disciplinary action. “I guess we do sometimes think: don’t upset that person too much … It’s not like we say that kind of thing in seriousness. It’s more like it’s almost a joke. Maybe a joke that’s funny because there’s a little bit of truth to it.” It’s interesting to see a decade later that my teachers complain and make the same kind of dark jokes in the teacher’s lounge as my friends and I did at lunch tables to cope.

Boykoff says fifth grade is a transition for students’ awareness of shootings. The teachers of the five year olds in kindergarten sing songs to keep them occupied through the drills. At lockout drills, where all the doors are locked but classrooms continue normally, teachers tell elementary students the exercise is to prepare for dangerous situations like a bear so they’re not too afraid. “The fifth graders, they know that it’s not a bear. They know the reason we’re doing it. So they kind of know what we’re doing when we sort of try to play it down.”

By 10 and 11 years old, children are exiting the naivety of childhood at different rates. It’s like believing in Santa. She can tell some parents tell their kids about shootings and others want them to be innocent about it as long as they can. It’s not up to her to tell them otherwise.

Boykoff describes the disconnection she’s felt from the endemic mass shootings, even while being a teacher charged with protecting students from them. “To be honest, the last, probably, seven or eight mass shootings, I shut down. I stopped paying attention to them because it was upsetting. I see it in the paper, okay, it happened. I don’t want to read the names…it’s like I just shut down.”

She and two other teachers brought flowers to the memorial site and ran into the funeral procession for the police officer who was killed, Eric Talley. This, she recalls, was when mass shootings were no longer an abstract concept to her. “Just it was sort of like a realisation like, wow, this really happened. It’s not just on the news. It’s not just something that happened somewhere else. Like it really happened. It really happened here.”

Many Boulder residents have reflected similar cycles of distancing from engaging with shootings. We’re so used to them, and yet to live and operate in society, we have to tell ourselves it won’t happen to us. As Maddie Davis conceives of predicting shootings: “We want to think it’s an irrational thought but it’s actually not, it’s completely rational.”

Boykoff says this reality exists in the back of her mind, but she has to continue staying in the present of being a good teacher. “It’s there. It’s sort of in the background. But not something I think about all the time. Every now and then when I’m on recess duty, I sort of scan the horizon. Looking around, because it’s so easy if you wanted to, like, shoot a bunch of kids, just drive up to the side of the school while their recesses start going. But no, it’s just more acute, like right after something happens.”

“I’d like to think that the Sandy Hook one was just one really crazy person that even other crazy people wouldn’t want to kill children. Maybe that’s wishful thinking.”

Indeed, discourse surrounding gun culture and mass shootings often includes the Sandy Hook Shooting in 2012 and the lack of change surrounding gun laws. Davis, who is 10 years my senior, wonders: “If there is gun violence that leads to the death of elementary-age students, and nothing changes, is change fucking possible?”

The horror of dead children contrasted with the inability of Congress to even pass a federal background checks bill, when 90 per cent of the public supported it, created a public hopelessness. It established that bringing a semi-automatic rifle into an elementary school to kill 20 children and six adults was acceptable.

But the very fact we’ve developed a script for the sorrow shows the way this has been acculturated into our everyday society because it’s been rehearsed so many times

Boykoff reflects on how she and other teachers got ready after the shooting to process the event with the students. When they came back from spring break, it was life back to normal. It was never brought up.

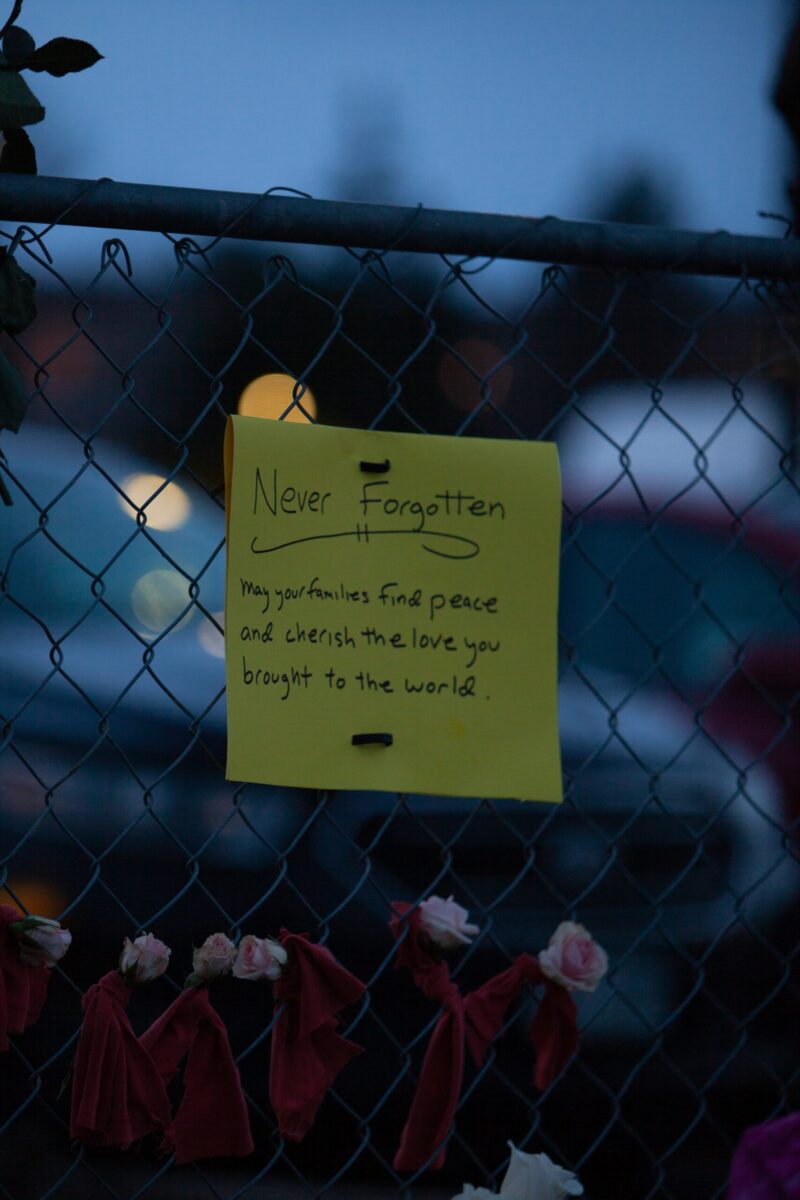

As I said, Americans are not heartless: we have candlelight vigils, lay flowers and notes at the scene of the crime. GoFundMe accounts are set up for family’s of the victims. Talk show hosts grow unnaturally somber.

But the very fact we’ve developed a script for the sorrow shows the way this has been acculturated into our everyday society because it’s been rehearsed so many times. I rant and rave to my non-American roommates about NRA lobbyists and my dad being an hour and a half away from death in a supermarket, but all they can muster in response is: “I don’t know what to say.” They don’t have the American script of gun violence mourning in hand, they’ve never had to rehearse this conversation.

We know how to act in response to an individual tragedy. We mourn. But after the shooting, many residents have little hope when it comes to stopping any shooting in the future. It’s less of a shock and more of a confirmation that even Boulder isn’t immune. Our anxiety over shootings has been legitimate all along.

After the shooting, I called my dad to ask how he’s doing. His brush with death is more of a confirmation of background anxieties than shocking. “At different points I have this awareness that because of the way things are in this country, at any time you go to any public setting you’re potentially a sitting duck. Because somebody … can have a gun and they have power over a room full of hundreds of people potentially. At any time, any place you go, grocery store, movie theatre, school, Pearl St mall. So yeah, I wasn’t surprised. On a visceral level, it was just this horrible sense of grief, ill-boding and rage, really pissed off. That’s what I went to bed with that night.”

However, with so many precedents of shootings with higher death tolls leading to no new legislation, it’s not rage that spurs hope. He’s raised a daughter in a country where school shootings are a common news item. He’s used to it.

Mass shooting culture means that part of the celebration of graduating high school is being glad your child is outside of an educational institution that puts a target on their back

“The whole time that you were in school here in Colorado and especially at Boulder High, every once in a while I was like: I hope I don’t come home and hear on the news something happened at Boulder High. That’s why when it happened at King Soopers I wasn’t surprised. There was part of me that was relieved when you graduated.”

Mass shooting culture means that part of the celebration of graduating high school isn’t the anticipation of college and reward for hard work and good grades. It’s being glad your child is outside of an educational institution that puts a target on their back.

“For me, and probably for mom, you represent our greatest sense of vulnerability.”

I ask him if he feels comfortable to return to the King Soopers pharmacy for his client’s prescriptions. “I can always say, well, lightning never strikes twice”, he says with a dark laugh. “It’s no different than going anywhere else. The vulnerability of going to the Table Mesa King Soopers is no different than the vulnerability of going to Safeway or the vulnerability of picking up something at Target, or the vulnerability of going to a Red Rocks concert.”

I now live in Ireland where even carrying pepper spray is illegal. It is now my parents living in Colorado who represent my greatest sense of vulnerability.

I didn’t realise how desensitised I was to violent the culture of mass shootings in America until I left. My new friends from around Europe didn’t laugh at the jokes I make about the absurdity of lockdown drills. When we tell each other stories of our lives in secondary school and some ask whether it’s really like High School Musical, I laugh and tell them not really – rather, it’s such a big country I can’t speak for everyone’s experience. What I can tell them is a universal fear of every American my age is being the kid stuck in the bathroom when the shooter comes. While your pants are down you hear it: “This is not a drill. I repeat, this is not a drill”, and by the time you leave the stall, the classroom doors are closing. You run from room to room pounding on the doors but no one will let you in because the teachers have been trained to not fall for shooters’ tricks. You are what they warned us of. If you go to the bathroom at the wrong time, you could die.

I know this is horrible. I know this isn’t normal. It’s only until I see the shock and horror on the non-American faces around me that it fully hits me how this isn’t a party story. Everyone there knew that the murder of innocent children at schools was reprehensible. Only I expected it.

Maddie Davis is now 30, and grew up in a Colorado public school system before lockdown drills. She went to the same high school as me. “I was still lucky enough to overall feel safe at school, for the time that I was there.”

There is a universal fear of every American my age is being the kid stuck in the bathroom when the shooter comes

It wasn’t until college when shootings became more frequent that she developed a fear and expectation. “Now I don’t feel safe anywhere crowded”, she tells me. She notes exits at grocery stores at malls and avoids movie theatres as they give her anxiety. The last couple of concerts she’s attended she eyes the security guards, wondering if they’re being sufficiently vigilant. “It’s just like you want to think: no, like they wouldn’t do it to this place. They wouldn’t do that here like this place is too sacred but … shooters have attacked young children, shooters have gone to nightclubs. For shooters there’s not really anywhere that’s too sacred.”

“If we were being realistic with ourselves about how valid that fear actually is, we would be petrified, all the time. Anytime we went anywhere. If we had to exist with that kind of paralysing fear, every time we left our homes, we wouldn’t do anything.”

She says she feels the anxiety but has to remind herself she’s been to so many concerts before and been completely safe and put the odds into perspective. “But I’m sure the shootings in the last decade, especially maybe the last five years, I guarantee a handful of people before they walked into the grocery store or whatever. I guarantee some of those people were thinking the same thing and removed it from their mind in the same way and then if fucking happened.”

After the news broke on the King Soopers shooting, Davis called everyone she knew who still lived in Boulder to make sure they were alright and recalls the emotions that washed through her: numbness at first, then anger at how this kind of occurrence, both tragic and routine, always ends up in a partisan squabble.

Joan Didion wrote of 1960s America: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” In today’s America, we have to tell ourselves the contradictory stories that shootings are common enough to prepare for and that one will never actually happen to us. One is a terrifying truth, one a self-soothing lie. Both are required in order to live. Americans tell themselves stories that they live in a just, safe society in order to go to the grocery store to buy dinner, to drop their kids off at school, to set up their classroom to greet their students. They also must tell the story of the possibility of the shooting enough times that they will feel prepared for it to happen.

The longer these shootings go on unchecked, the more a protective culture is formed, the closer reality has to come to break free of the narrative. My mom never cried at the shooting. She doesn’t have the hope and trust in the value of lives that created the disturbance she had for the Columbine Shooting in 1999.

I cannot explain all this to my taxi driver after a night out when he hears my accent and begins to grill me: freedom and slavery, all lives matter but not refugee’s, pro-life and pro-death penalty. “I come from a mad place”, is all I can offer him beyond a tip as I step out of the lift into the night air of Dublin. And it is mad. It is, as my mother repeatedly spits into the phone, “sick.” We have formed a culture to try and make sense of it. We have swept it up under the carpet of doublethink. But there is darkness lurking. It is a testament to its gloom how much we work to avoid it. The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

My sentiments are the same as everyone I’ve spoken to. I am part of this culture. While I know rationally potentially at any time my family and friends back home could be the victim of the shooting and there’s little to stop it, the existential dread I feel everytime I sit down to write about the very real example of my dad is something I want to avoid. Yet, I was removed from the culture enough to be surprised when I went home for the summer three months after the attack that everyone else wanted to push it away as well. No one spoke of it. Many people said I was the first to bring it up in months. I expected to come back to a mourning city and instead found the home I’d always lived in, with just some businesses shut due to coronavirus and a sticker sold in my neighborhood bakery that raised money for victims’ families.

But of course they’re still grieving – they just have to continue to live. The Table Mesa King Soopers won’t be torn down as some suggested, but will be completely remodeled inside. I reached out to a former high school teacher and she declined my invitation to interview because, due to coronavirus and her schedule, she hasn’t had to do a lockdown drill in awhile. But she wrote: “Honestly, I’m just not sure that I can gather my thoughts in a way that I’ll be able to express easily.” I spoke again to Boykoff in the fall and she wrote that she hadn’t heard anyone talk about the shooting in a couple of months. They have to go back to life, teachers are too busy making a new curriculum and teaching children who’ve been learning on Zoom for over a year. We’re grieving, the fact we’ve pushed it to the back of our minds or that we can’t bring ourselves to talk about it is a testament to how raw it is. This culture we have created is a way of getting through the day.

Mass shooting culture is protective, a way for everyday citizens to prevent themselves from breaking down amidst the “this happens constantly, but it won’t happen to me” paradox. But I worry it can be part of perpetuating shootings by making the populace they target completely disillusioned. Davis comments on this feeling, coupled with other political issues having no change despite popular support: “I think it’s maybe just like my own sense of defeat, that’s kind of like: well what can I even do? But I think if I’m being realistic, there is a lot more action that can be done on the local level.”

When my father told me of how he was one cancelled meeting away from being at the shooting, he made me promise I wouldn’t tell my mom. When I asked why, he said she’d freak out. He wanted her to keep a hold of the story she told herself to live. He found no need to disrupt that story when in all likelihood, this new, real story would have no ending that could guarantee his safety or hers in the future. On the eve of publishing this article seven months later, I had to tell her.

After the shooting and throughout the months between it, she describes her reaction as a numb one, almost disturbing herself by how distanced she feels to it. She says she never cried or emotionally engaged like some of her friends did. But she is furious: my transcripts of our phone calls are filled with righteous expletives. But she notes the moments where she is confronted with the reality – through our interviews, or when someone has a connection to the shooting. She has a co-worker who used to work at the grocery store and knew people who were killed. She sees her grieving and sometimes they talk during breaks. “I was just brought right back when she spoke about how fucked up that was that her friends were killed, and you just don’t relate to it until – boom – you relate to it.”

“But then after talking with you, I have to do something else – I can’t be in this. I think maybe some people are just like, it’s just not going to get better. So, taking action, it just seems kind of hopeless.”

I want my mom to have no secondary trauma to retreat from in order to get through her shift at work. Part of me wants to protect her in the way these stories do, this culture does, how my dad tried and kept her in blissful ignorance. But I tell her how close we got.

She’s silent for a while. “Wow. People were killed. People kill people’s husbands.” She’s in tears on our FaceTime call. She thinks of a couple she saw on the news who were engaged who were killed in the store. “Again, it doesn’t hit me, and then you tell me that story. It’s like, is that when we take action, when one of our loved ones almost dies?”

“That hits at home. It’s incredibly close. He would have been at the pharmacy, which was where a lot of the shooting happened … I mean me and dad are curmudgeons, but here’s my man, you know, he’s my soulmate.”

I ask her how she feels now. “I feel frightened and angry in a way that’s different, when I check out it’s more distant, a distant fear.”

My mom’s glad he didn’t tell her at the time of the shooting. To keep emotionally engaging with something hurtful with no end in sight is a kind of self-flagellation. I want to offer her some consolation. I don’t want her to hurt. But without the hurt, without any of us Americans truly facing how normalised mass shootings are and how terrible that reality is, I don’t know if we will be disturbed enough to enact change.