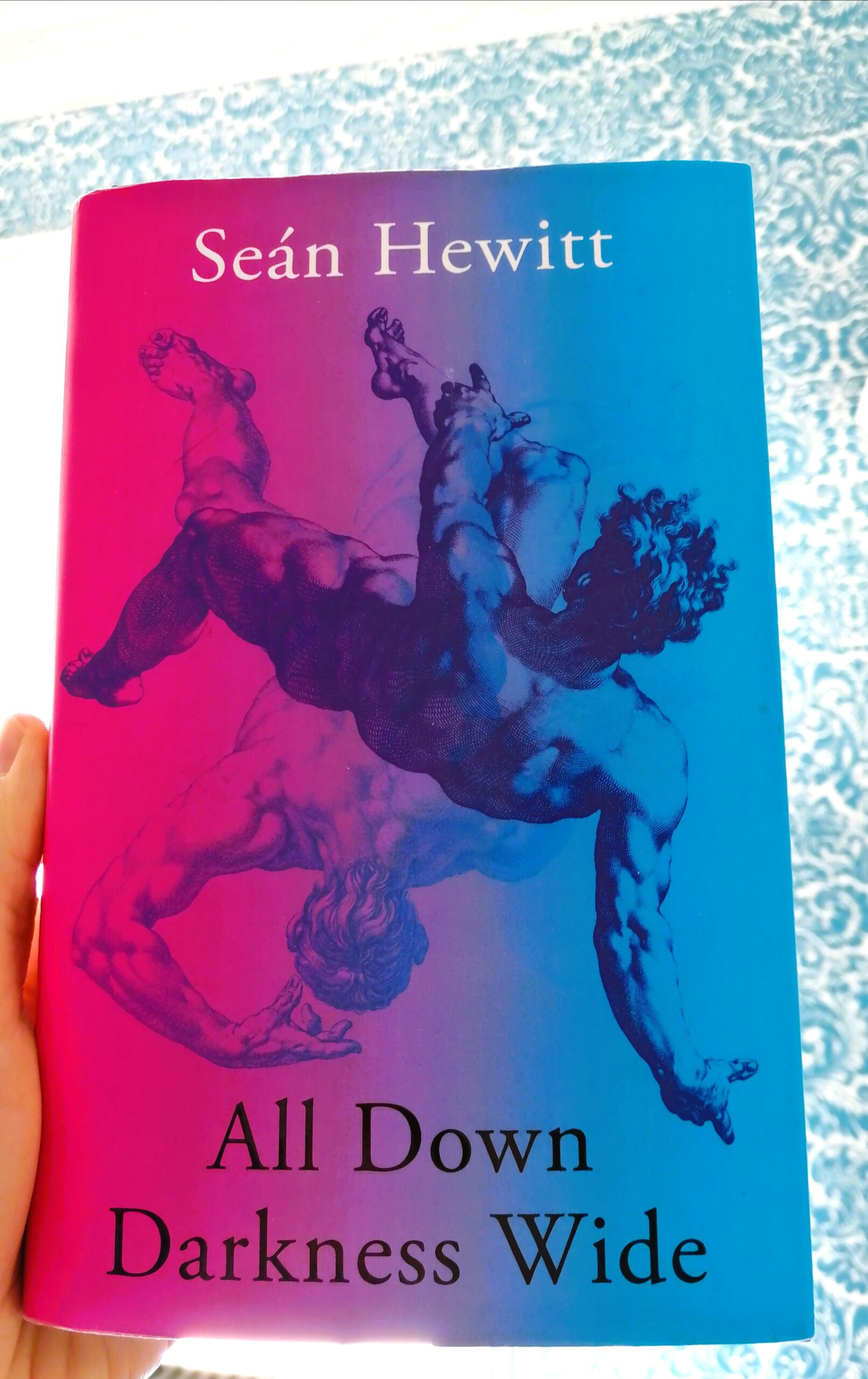

Rather than shying away from intimate, puzzling and painful life experiences, Seán Hewitt’s memoir All Down Darkness Wide draws inspiration from them, weaving together life and literature while exploring a range of themes, including queer identity and mental health, and offering insights into Hewitt’s own experiences. The memoir is both extremely personal while also acknowledging shared experiences that are too often overlooked or unexpressed. To learn more about the memoir and the process behind it, The University Times sat down with Hewitt to explore these themes in greater detail and hear the author’s own perspective.

When his memoir was published, Hewitt had already been awarded the Laurel Prize for his collection of poems Tongues of Fire, but the process of writing All Down Darkness Wide went hand in hand with his poetry. As Hewitt explains, his writing registers what happens in his life, and his memoir took him almost five years to write, resulting in overlaps between the two books. I found that the poems “Ghost” and “Old Croghan Man” in particular feed into the shared experience and histories of queer people that occupy centre stage in the memoir.

“In some ways”, says the author, “All Down Darkness Wide is a companion piece to Tongues of Fire that gives you a fuller context that the poems don’t need, as they can live on their own”.

Subverting the Gothic tradition in which frightened spectres demand vengeance from the living, the ghosts in this memoir are reassuring figures who witness a certain kinship

Spanning continents and times, Hewitt’s memoir recounts his relationship with Elias, a young Swedish man, and how Elias’ struggle with depression influenced their lives. It opens up for past and present to meet in the common ground of queer experience. It makes no pretensions to speak for what the author describes as “an incredibly varied collective”, but rather it gives resonance to personal and communal queer stories. In the same way a rhapsody blends multiple songs into one coherent piece, Hewitt gathers stories from different individuals and weaves them together into one big literary tapestry.

Elaborating on this, Hewitt adds: “I began to look for people in the past that had gone through similar experiences to my own and to look at the cycles of history, but also at the ways in which you might break through a cycle.” This echoes the other thread of the memoir – the author’s liberation from the fictionalised self he created based on societal expectations that leads to a reconciliation with his authentic self.

Hewitt develops a particularly significant relationship with poets from the past. “We’re often taught that we can choose our own family as queer people, but I liked the idea of choosing our own ancestors as well, because we don’t have biological relations to the identity categories that we have”, he explains. This reflects the strong presence of ghosts in All Down Darkness Wide. Subverting the Gothic tradition in which frightened spectres demand vengeance from the living, the ghosts in this memoir are reassuring figures who witness a certain kinship, a connection that reminded me of Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat.

In the same way a rhapsody blends multiple songs into one coherent piece, Hewitt gathers stories from different individuals and weaves them together into one big literary tapestry

“We often think of memoir or non-fiction writing as being solely in the realm of the real”, the writer muses, “but I think that there are times in our life when we think Gothic-ly. It was a way of getting to the truth of experience rather than just the truth of facts. I liked the idea that the memoir might bend a little bit to allow those ghosts in”.

All Down Darkness Wide also engages with the underlying idea of translation. Putting life into words is arguably a form of self-translation, and Hewitt uses this as a narrative device in one of the most dramatic moments of his book when, in the depths of Elias’ depression, communication fails. If Victorian writer Gerard Manley Hopkins informs the rest of the memoir, starting with its title, it is Swedish writer Karin Boye’s words that grant new meaning here, and their translation enables “a shared language when otherwise it seemed impossible”.

The translation of Boye’s verses into English becomes a shared act between Hewitt and Elias, bringing meaning to a shared situation. Discussing his experience of translating Boye’s poems about anguish and depression, he described her as “an intercessor”, a ghost between himself and Elias.

“We often think of memoir or non-fiction as being solely in the realm of the real, but I think that there are times in our life when we think Gothic-ly”

While writing his memoir, Hewitt “was able to put language on experiences and emotions that had never existed inside language for me before”, and therefore to look into “the terror of mental illness, that can often be untranslatable”. Indeed, All Down Darkness Wide gives visibility to issues too often kept silent, recognising intersections between the author’s own life and the experiences of individuals who went through similar experiences, especially since Hopkins himself “is until quite recently not spoken of as a gay poet”.

In keeping with the spirit of All Down Darkness Wide and Hopkins’ poem “The Lantern out of Doors”, the memoir almost acts as a lantern itself in that it is very likely to become the book people look for to understand and explore their shared experiences.