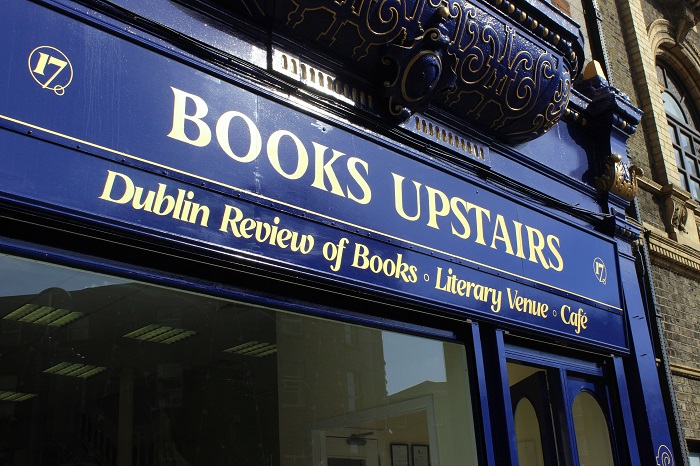

When an eighteen-year-old Louise Nealon told a GP she was having dreams that didn’t feel like her own, he gave her “a prescription to read Marian Keyes” (and antidepressants). The intimate relationship between our brains and our bookshelves was the matter at hand in Books Upstairs on Wednesday evening. Nealon joined fellow authors Molly Hennigan and Charlene Hurtubise for a discussion on writing – and, inevitably, reading – women’s mental health, moderated by Eiru publishing director Deidre Nolan.

Although all three authors have written books which incorporate mental illness, they exemplify that ‘mental health’ is far from a monolith. Nealon said she has “a problem with the term mental illness or mental health because it suggests that it is easily definable or can boil down to one person.” The variation between and within the three writers’ books highlight the inadequacies of a catch-all comprehension of women’s minds. Hurtubise explained that “there is one person clearly struggling with their mental illness in my book, but there are a lot of people drowning in their everyday lives.” She was inspired to write her novel, The Polite Act of Drowning, after reading that drowning is “almost always a quiet event” – so too can struggles with mental health sometimes manifest as a whisper rather than a scream.

Hennigan’s book, The Celestial Realm, also partly considers silence: those who it has been thrust upon unwillfully. When she visited her much loved grandmother in the psychiatric hospital she was a patient at, the voices, theories and stories she heard were often passed off as madness. Instead, she asked: “what if it isn’t?” In her essay for the Stinging Fly which preceded the book (and forged the friendship between herself and Nealon) she writes: “We talk about silencing Irish women and it is almost always metaphoric, or rather representative of a particular type of non-hearing […] Let’s also talk about the women’s voices that were physically silenced. The women whose ability to communicate was severed by drilling into the skull.” And the discussion on Wednesday did not shy away from the dark realities of psychological struggle. Hurtubise described depression frankly – “it’s a takeover” – and explained how re-reading a particularly grim scene in The Bell Jar “was a frightening moment because I recognised it”.

However, the authors also lauded literature as a beacon of comfort. Nealon told the room that “whenever I felt mad I read, and I felt less mad because I felt seen”. Hennigan explained that a lot of what she enjoys watching or reading in regards to mental illness falls into the category of comedy. She expressed that these were just as instructive for her as more ‘serious’ works. All three women reiterated Nealon’s assertion that “what was medicinal for me was reading”.

Writing, however, was a little more complicated. Although Hurtubise acknowledged that creating her novel “was catharsis” and Nealon said that she finds it “much easier and more helpful to talk about mental health through the lives of fictional characters”, everyone laughed when asked how they maintained their sanity throughout the writing process. Hennigan admitted that publishing a book with such personal themes “can be scary, especially when it’s non-fiction.” She also acknowledged her concerns about writing “about my real experiences in an indulgent way”, aiming instead for “spare and light” prose. Nealon acknowledged that “the ‘maddest’ character [in her novel Snowflake], Maeve, doesn’t actually get a lot of scenes because I did find it difficult to write her.” What was overwhelmingly clear from the evening, however, was how essential writing through these difficulties is. Where these authors have woven tales of mental health into wider narratives and characters, they have also contributed to a tradition of reading as solace and making sense of oneself.