During his inaugural speech in April 2011, Patrick Prendergast gave voice to the themes that would shade his image and guide his actions for the following decade. He committed himself to acting as a steward of Trinity’s enduring tradition while also re-invigorating College’s image, putting it on par with universities like Harvard and the Sorbonne.

Focused and pragmatic, Prendergast had a self-understanding as an actor within the fabric of history at Trinity. But despite criticism of the commercial decisions he incorporated in his capital development plan, Prendergast’s economic stewardship must be understood as a product of the successive cuts to third-level funding and of progressive desperation.

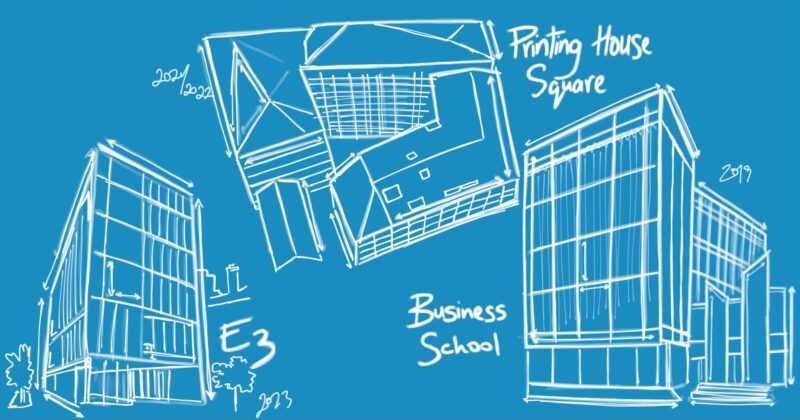

Early interest in infrastructural development was situated as a component of the Provost’s larger project to bolster Trinity’s wider reputation. New, modern buildings on the College campus would breathe new life into spaces that had historical value but were not functionally beneficial. They would provide more teaching space, research facilities and add spaces for corporate functions or private rental.

But student perception rarely harmonised with the visionary changes he launched to re-imagine a new funding system at Trinity, buoyed and distinguished in part by a rake of capital projects. What became animated issues for students were the restricted, semi-accessible and worn-down existing buildings across campus.

Prendergast constructed upwards, in a climate grounded in salary cuts and dire reductions in public funding, inspiring corporate comparisons. Nikolai Trigoub, the president of Trinity College Dublin Students’ Union (TCDSU) in 2010/11 explains: “You can’t focus on capital projects when you’re worried about basic funding, just keeping the university running.”

New, modern buildings on the College campus would breathe new life into spaces that had historical value but were not functionally beneficial

The funding model for Inspiring Generations projects like the Trinity St. James’s Cancer Institute and E3 Learning Foundry involve financing from philanthropy and borrowing from the European Investment Bank, which can then be matched or exceeded by the state.

The Old Library redevelopment project, requiring ground-floor transformation to develop a research collection study centre, and the Book of Kells display, follows this model closely. Recently, the state committed to a €25 million fund for the project, indicating that Prendergast’s efforts to make Trinity’s case to the government were fruitful. Brian Lucey explains that Prendergast “became one of the few university presidents that was willing to stand up and take the fight to the government to say, funding is a problem. And you’re going to have to do something”.

Maintenance programs on buildings like the Old Library matched with new developments. Trinity East, for example, is a slower project that the Provost has conceded was “going to take decades”.

“The Board”, he said at a retrospective review event, “has decided that they have to take a long-term view in developing that site as a university campus, not as a property play, but an extension of development of the main campus, done carefully, with lots of deliberation over time”.

As implications of the economic crash intersected and fiscal constraints mounted early on, Prendergast launched a new phase of action focused around generating funding. He not only secured funding for individual development endeavours, in particular capitalising on a generous alumni network, but inspired momentum for more government contributions.

The Board has decided that they have to take a long-term view in developing that site as a university campus, not as a property play

“Philanthropy has been a game changer”, College’s Director of Communications Tom Molloy explains. “Philanthropy puts it up to the government to match that money”, offering “tremendous leverage” to launch new capital ventures, including securing €25 million from the government.

Prendergast moved construction projects based in science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM), in particular, higher on the academic agenda. The latest financial statement published by Trinity indicates that spending on capital projects in 2019/20 reached €67.3 million. Despite such escalating costs, this figure must be balanced against the recent renewal of construction projects such as the E3 Learning Foundry.

After the ceremonial sod-turning last month, construction can officially begin on the Learning Foundry. The project will facilitate an additional 1,600 students studying STEM to confront environmental and societal problems in a building designed for achieving sustainable structural operation.

Former TCDSU President Kevin Keane explains that “the emphasis on capital projects was dramatic and has delivered properties and some new spaces that will probably be valuable for the university for the next 100 years”.

Prendergast admits “I would have liked to cut the ribbon on Printing House Square”

Proactive infrastructure projects were realised before the eyes of students walking across campus. At the same time, however, an undercurrent of unrest over unaffordable housing wedged a divide between the visual and structural changes to Trinity’s campus, and the lived experience of many of its students.

One of several major recent construction projects in Trinity is the new 250-bed student accommodation, Printing House Square. The building bridges historical granite materiality and contemporary facades, as well as acting as a gateway between the College and the city from Pearse St. It will include a health centre and the Disability Service, as well as new sports facilities and amenities. With a target opening set for September 30th, Prendergast admits “I would have liked to cut the ribbon on Printing House Square”.

Dogged by delays, Printing House Square was the source of many embarrassing headlines for Prendergast. Construction setbacks were arguably out of his control – as was the shutdown of all building sites due to the pandemic – but labour rows raised questions over how hands-on Trinity is with contractors, or should be.

Various College groups are eagerly awaiting the building’s completion so they can move in, but Prendergast’s successor Linda Doyle would do well to ensure that Printing House Square is actually suitable for its occupants’ needs before they’re allowed in, lest a repeat of the early days of the new building for Trinity Business School should occur. The business building was a mammoth undertaking from a financial perspective – it was delivered, as Lucey points out, without any state funding.

Lucey, a professor in Trinity Business School, adds that it was “the ability to re-invest a significant chunk of surplus funds, of incremental surplus funds, back into the school … That’s what allowed the school to build the new business school, both in terms of the building and the faculty, without a single penny of state money”.

The business building was a mammoth undertaking from a financial perspective – it was delivered, as Lucey points out, without any state funding

Despite innovative funding schemes, the business building quickly came under scrutiny by students for its insufficient study spaces and poorly equipped lecture halls. Physical structures, students argued, needed to be primarily conducive to student living and learning. Some of these concerns were simply teething problems, and Prendergast has since said that he regrets not becoming a student advocate sooner.

Giving physical expression to Trinity values by expanding the spaces for research, education, intellectual curiosity and student living became a point of concern for students – and while Prendergast publicly lauds his drive to secure such spaces, the reality was that students constantly felt seconded by tourists and visitors with cash in hand.

Indeed, 2019 was the year that the number of tourists on campus piqued Prendergast’s concern. “Of course, we want to provide for the tourists that come into the College”, he explains. But certain spots should be off limits to tourists, or at least monitored: “Really, the Arts Block should be primarily a place for students to congregate, meet, talk, discuss, do the things that students do as part of the student experience … it’s a balance between the two.”

Crowds of tourists in Front Square, he conceded, detract from the nostalgic intimacy of campus.

College Bursar and Director of Strategic Initiative Veronica Campbell also adds that it was a matter of finding a happy medium between providing student bases and capitalising on the central location and historic relevance of Trinity to encourage tourism. “[We] don’t want to be doing anything that’s damaging the student experience and our academic activities, and [damaging] for the commercial gain.”

Really, the Arts Block should be primarily a place for students

Establishing student spaces and making accessible the complicated features of the Trinity estate is a priority. Campbell explains that refurbishment of the Rubrics, the oldest remaining building on campus, is next. “We’ve just appointed a contractor to do a refurbishment of that project and … to make sure that we’re able to continue to use it.”

A feasibility study is planned for House Six, where TCDSU is based. Such studies have previously been conducted in individual cases at the 1937 Reading Room and the Graduates Memorial Building (GMB). Accessibility issues prevail, however, and the task of characterising structural improvements to facility student use persists. “We’re never going to be knocking down the buildings [of] that historic campus so we need to make sure that we continue to have them operational in a way that best suits a modern university”, Campbell explained.

Provosts may be credited with launching projects, the conclusion of which may elude them during their tenure. Prendergast perhaps understands his role within a tradition, a series of generational cycles. Despite his understated exit, he has ensured that the path he has paved will progress in the direction he has launched: expansion. Although his intensely focused approach to capital projects underpinned the selection, scheduling and pace of development, Prendergast ensured that the course he had set would exceed his tenure.

But in the rush to characterise an era launched and concluded in crisis, the interdependence of provost legacies cannot be forgotten. Despite the consistent construction, these physical markers of progress rising from an economically stagnant Ireland were deliberate efforts to carve out a new path for Trinity. Although inflected with personal preferences, this path primarily sought capital ventures that would generate new income while also entrenching Trinity’s autonomy. Whether out of personal conviction or necessity, such a course widened the disjoint between the lived student experience and the slow but progressively moving wheels on the staple capital ventures of his tenure.

Naoise D’Arcy, Mairead Maguire, Emma Taggart and Emer Moreau also contributed to this piece.