In 2013, a book was published called Trinity Tales: Trinity College Dublin in the Eighties. In it is an anecdote from none other than our Provost, Patrick Prendergast, about a prank his class played during his student days in Trinity. Trying to find the book before our interview proves practically impossible. Trawling through College’s library database turned up nothing, and after the shop assistant in Hodges Figgis claimed to have never heard of it, I began to sense a conspiracy.

Eventually, after hours searching, I found it. The prank, it turns out, involved a kissogram, a lecturer and a packed out classroom – the kind of prank that might make headlines in The University Times if it happened today. When I bring it up in our interview, the Provost cringes slightly: “There was a fad in the 1980s of kissograms and what this would involve typically – it’s terrible to relate it now, but it was a prank that probably wouldn’t be very PC now – but generally it involved a woman coming in to kiss a lecturer.”

“Thanks be to God that we don’t do that anymore”, he adds. Indeed.

By all accounts, the Provost had an otherwise normal Trinity experience. A young lad up from the country, some indulgences in alcohol and student activism and a healthy interest in society life. So how did he find his first year in the College? “I found it exhilarating and challenging. Academically, what I found was that, of course, the material came at you fast and furious. You were given whole books to read in the space of a lecture”.

It was radical, it was at the edge, it was pushing the boundaries, and it was the only university in Ireland in a way that was so upfront at this

Life in Dublin was very different from his school days in Wexford: “When I came to Dublin I was in a flat and living with two other guys, and we had freedom like we’d never had, and we used it to maximum effect.” It’s not too difficult to imagine what this freedom was used for: “There was a rowdy social scene, revolved a lot around drinking, which probably wasn’t good.” He says: “It’s good that things have kind of changed. We would be handing out leaflets in Front Square about ‘Join the Phil and drink your fee in the first half hour, that sort of thing’. We wouldn’t be doing that now.”

Yet Prendergast was also passionate about his chosen course: engineering. Describing himself as “rather studious”, he admits he “really did find the explanations of how things worked and how the world worked from an engineering point of view extremely interesting and that motivated me to study it”.

It wasn’t just the course that attracted him. Trinity was changing in the 1980s, becoming larger and more international. “There were years in Trinity, decades perhaps in the early part of the 1900s, when there were no new buildings built, there was just no money. And that was the same around the country”, he says. Yet when Prendergast arrived in 1983, he found a “palpable sense that the country was moving”.

If Ireland was developing socially too, the pace was glacial compared to Trinity. In a world before divorce was legal and contraception wasn’t widely sold, there must have been something thrilling about Trinity. It certainly made an impression on the Provost during his time here: “The students’ union shop, and I think the Virgin Megastore, were the only two places in Dublin selling condoms in a vending machine. And this is what Trinity was like. It was radical, it was at the edge, it was pushing the boundaries, and it was the only university in Ireland in a way that was so upfront at this.”

Around the room, other Provosts stare down at us. The dour frown of Archbishop Adam Loftus, the first Provost, is particularly intimidating. I wonder how many of them would have approved of their successor recounting tales of kissograms and condom machines to a journalist.

I remember walking with many other students chanting ‘Mandela will be free, Mandela will be free, Mandela will be free’ around Trinity and up to the Mansion House

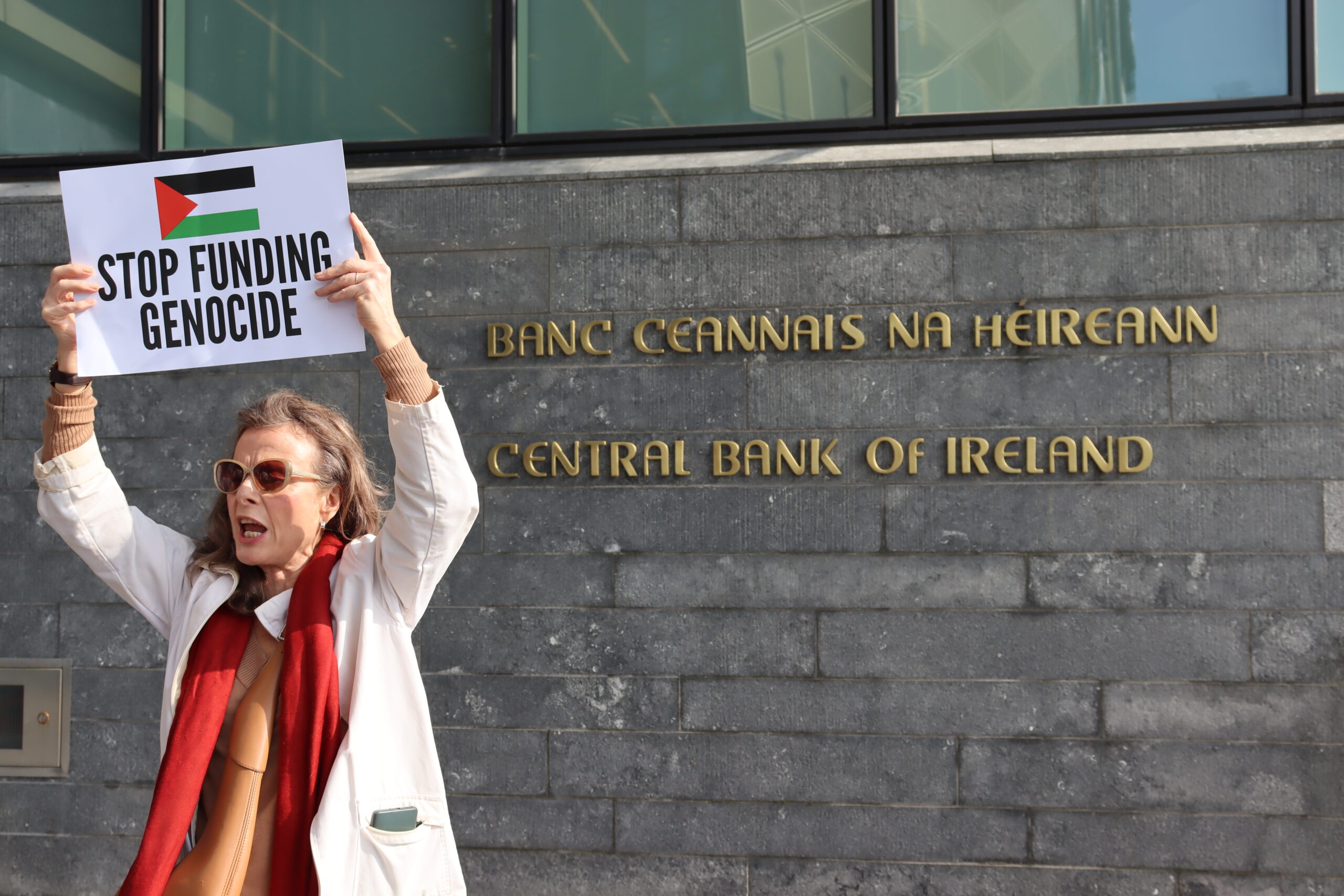

This radicalism is what many associate with Trinity in the 80s. So how proficient was our Provost with a loudspeaker and placard?

“I remember walking with many other students chanting ‘Mandela will be free, Mandela will be free, Mandela will be free’ around Trinity and up to the Mansion House”, he says. Not that he would have described himself as “heavily political engaged” at the time. Despite this the young Prendergast appreciated the value of student politics: “We knew who our Faculty Convenor was, and they often came in and told us what the issues were and how they were pursuing them with the College authorities”.

Now that the tables have turned, and Prendergast is the one facing these student representatives across the table, he still values this political energy. If during his time, “there was a sense among students that the future is for them”, then, he tells me “that’s something that we in Trinity have always encouraged, and under my Provostship, are continuing to encourage.” Indeed, he references the work of TCD Fossil Free, describing the “fierce pressure” the group have put the college’s senior management under to divest from fossil fuels.

I find it hard to pin down what exactly why Prendergast loves Trinity. In many ways it seems as if the thrill he felt entering the university as a first year never left him. As a young researcher he jumped at the chance to return to Ireland from the Netherlands when a faculty position came up in the School of Engineering, the first for 10 years: “I thought ‘God, I better apply for this or there’ll never be another one coming up.’”

Take everything that Trinity has to offer. It’s a great institution. And to the new students: you’re part of a long tradition and a great institution that you can not only gain from, but give to

“Gritty” Dublin also drew him back: “I certainly felt that if the opportunity arose to have my career in Ireland and contribute to this country and education in Ireland, I would take that.”

Since the Celtic Tiger ended, Irish higher education has been blighted by problems: underfunded, lacking student accommodation and collapsing in global rankings. While it’s easy to be cynical about the future of higher education in Ireland, the Provost is optimistic. Trinity, he says, will always maintain the “values” of a modern university, despite what changes the future may bring: “The value of independence of mind, the values that we’re international, that we’re globally connected.”

Unsurprisingly then,The Provost’s advice to first-year students is optimistic: “Take everything that Trinity has to offer. It’s a great institution. And to the new students: you’re part of a long tradition and a great institution that you can not only gain from, but give to.”

I ask him whether he would have listened to such advice had it come from his Provost in 1983. He mulls it over: “Life holds many opportunities, and you’ve got to keep alert to those and pursue them when they present themselves.” As advice to new students go, it’s certainly worth repeating.