The publication of the government’s higher education funding working group report in July marked a turning moment in the way we talk about how Ireland’s third-level institutions are run. As the amount of state funding fell drastically, higher education institutions found themselves caught in a trap that saw them unable to speak out as resources and quality dwindled. They fell in the rankings and began to adopt controversial strategies, such as increasing commercialisation activities and the number of non-EU students. Universities continued to stay silent, even in the face of mounting criticism, hoping that the €1 billion that is now needed by 2030 to sustain the higher education sector would come quickly.

The conversation has since shifted, with the report’s publication thrusting the issue into the public eye. After September’s QS world rankings, which saw Trinity fall 20 places to 98th and University College Dublin (UCD) fall 22 places to 176th, Provost Patrick Prendergast and UCD President, Andrew Deeks, issued a joint statement, which ended in an appeal to the government: “A significant start has to be made in the forthcoming budget to signal that the government is serious about investing in our young people and providing them with the skills needed to survive and thrive in an increasingly competitive global environment. The future of the country depends on it.”

This watershed moment was supposed to come earlier. The report’s publication was delayed by over six months, prompting trade unions and a working group member to call for its immediate publication in May. When published, the Dáil was just about to go into summer recess, and the return has seen the coalition government attempting to figure out where it stands. Until last week, with the publication of the Action Plan on Education, there was no set timeline in place for the Education and Skills Committee, to whom the responsibility for settling on a funding model has been passed, to decide on an option, never mind going about implementing it. With the plan, Bruton has now said that the new model should be decided upon and implemented by the second quarter of 2017.

I think also that the colleges have to demonstrate their capacity to impact on the ambitions of the country, that’s going to be a big part of winning the argument for the secure funding flows

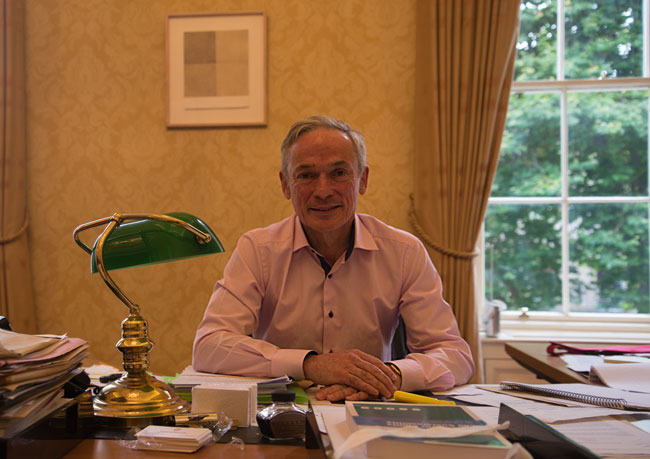

Speaking to The University Times, Bruton is clear that a decision needs to be made, and soon: “I’m very keen that the committee would have hearings quickly. I mean, obviously there’s been some disruption in the Dáil, the long period to set up the government in place, committee secretariats are only being established and so on. So I know the committee will have a lot of work, but I’d be very keen to have it moved quickly.”

Moving quickly, however, requires political consensus. Bruton acknowledges this, highlighting how “we already see that parties will be coming with different views”. While a clear consensus may not have emerged, however, what has been made clear is that every other party that has representatives on the Education and Skills Committee – the Green Party, Sinn Féin, Labour and Fianna Fáíl – have all advocated for systems that do not include an income-contingent student loan scheme, one of the three options the report presents alongside the creation of a predominantly state-funded system, the continuation of the current student contribution charge coupled with increased state investment. In contrast, Fine Gael has not committed itself to any model of higher education funding, although a draft of its education manifesto in advance of the general election did advocate for a student loan scheme.

Bruton acknowledges that “Fine Gael hasn’t expressed a view on the Cassells report”, adding that the party has “been open to the alternative funding mechanisms that Cassells has talked of, so we don’t come with a closed mind on any of the options”. He states that he is open to a compromise on the options, leaving the door open for a model different to one of the three that are being debated in the public sphere, something that could result in further delays.

The decision to pass the Cassells report to the committee has been interpreted as a politically advantageous one, with blame for any decisions made shifting from Fine Gael to a cross-party group instead. Others have stated that such a shift will delay what needs to be an urgently made decision. Bruton acknowledges the urgency needed, while stating that finding a consensus on the topic is vital: “Those who are advocating getting started also have to be willing to advocate for the solution they feel is right and demonstrate how that can work and support that. I don’t think people can sit on the sidelines and say ‘well that’s for politicians now to solve’.”

I hope that stakeholders don’t form opinions of me based on some preconceptions and instead engage with what I’m trying to do

The problem, however, is that the group was set up to produce three clear options. What’s the point in waiting for years for such a report and delaying its publication for months, only to start the debate all over again? Indeed, IMPACT organiser, former President of the Union of Students in Ireland (USI) and a member of the Cassells working group, Joe O’Conner, criticised the idea of compromising on any of the reports options when speaking to The University Times on the report’s publication: “I certainly would not like to see a scenario where the committee does the work of the expert group again. I don’t think that’s its role. I think its role is to look at the options, assess them and make a choice.”

Bruton, however, remains all about consensus: “This is a community challenge. We, as a community, have the ambition to see people progress in our education, to have [the] best quality education, so I think it’s not enough for people to say ‘well, you go and fix it’. And I think also that the colleges have to demonstrate their capacity to impact on the ambitions of the country, that’s going to be a big part of winning the argument for the secure funding flows. So it’s not just demanding action but showing that if we can win some extra funding, it will impact.”

When Bruton was announced as the new Minister for Education and Skills in May, many education activists and union leaders who support a publicly funded model of higher education expressed concerns at the stance of the party, and this idea that colleges would have to justify their own work. Then-President of USI, Kevin Donoghue, noted to The University Times that “a Fine Gael Minister for Education presents some challenges in that, from a funding perspective, their objectives wouldn’t necessarily have lined up with ours in the past”.

It was, however, not just Fine Gael’s approach as a party to higher education funding that had raised concerns, but Bruton’s own background in trade and job creation. Mike Jennings, General Secretary of the Irish Federation of University Teachers (IFUT), stated to The University Times that he was “a bit worried” and that Bruton “hopefully will have to change his political direction if he is going to understand the dynamic of higher education”. A former Minister for Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation and researcher at the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), some, including Jennings, have seen Bruton as someone who “views higher education as simply training, preparation for people to get short-to-medium term jobs, and that would be a disastrous undervaluing of higher education”.

Bruton, however, rejects this characterisation: “I may have done a certain job in the past, but I come with having been a spokesman on education back in the early 2000s, having published on early school leaving, on literacy problems, on problems in STEM within our education system.”

“My policy paper ‘Not Just Another Brick in the Wall’ was very much focused on how we open up education to impact on the lives of people. So I think they may have a very limited record of what I’ve taken an interest in in politics. But if they go back and look before I was in enterprise and when I was in education, I think they’d see how much more broad [my policies are]”, he continues. “I hope that stakeholders don’t form opinions of me based on some preconceptions and instead engage with what I’m trying to do.”

Some of these elements of Bruton’s background appear to have influenced his approach to the kinds of reforms that third-level education could benefit from. He states that “we need to see much stronger links between the education services and the world of work and the world of community and the world of culture, public service in particular. I would like to see much more placement for example in public service institutions as part of people’s education”.

“I think the real world can play [more of a] role in allowing people make the right choices when they go to college. I’m not sure that we presently equip people well enough to make the choices. I think there could be much stronger links to allow people to understand what are the job options when they make choices in education, and there are, unfortunately, high dropout rates”, he continues.

I think a lot of the successes in access have been around well-designed access programmes with support and mentoring and involvement and setting high ambition in areas… so I think it isn’t as simple as saying which funding model at higher education

Since starting in the role, Bruton has also put a large emphasis on improving access to higher education. Speaking in Trinity alongside Provost Patrick Prendergast as well as the presidents of Boston College and Georgia Institute of Technology at the beginning of September, Bruton spoke on the importance of improving such access. “One goal is undoubtedly our capacity to bring people from disadvantaged communities through our education system”, he stated, adding “as we look to education, one of the key challenges that we face is how we can be more inclusive of people who perhaps through disadvantage or disability haven’t to date achieved their full capability”. The Action Plan for Education sets targets to increase the numbers of these students entering the system, including increasing the number of Travellers in higher education from 35 to 80 by 2019 and increasing the proportion of students with disabilities as a percentage of all entrants to higher education from six per cent to eight per cent within the same time period.

Many proponents of the “free fees” model would argue that a fully state-funded system is the only funding model that would improve this kind of access to higher education. Bruton, however, states such an assertion “has to be teased out”. “I think a lot of the successes in access have been around well-designed access programmes with support and mentoring and involvement and setting high ambition in areas, so showing they can be done, role models who demonstrate that, so I think it isn’t as simple as saying which funding model at higher education”, he continues. More complex structures will be needed, Bruton said, rather than simply one model or another, “to deliver equality access” to higher education.

Ultimately, Bruton states that education is key to the government’s plans for the country: “If you can bring people through their education system to greater progression, reduce their chances of unemployment, increase their income capacity, you deliver. I see it as being absolutely important … not just higher education, but the whole education piece is central to that government ambition.”

For this to happen, funding is vital: “We do need to find a way to be able to fund potentially a 25 per cent increase in enrolment, or even up to 30 per cent on some views. We do need to be able to meet skills or innovation challenges, we do need to bring people who have been locked out of the system, give them a better chance of participating.” As we wait for that consensus to arrive, those crying out for funding will hope that the conversation won’t shift once again.