In these days of hyperconnectedness and polarisation, we are always under pressure to not only have strong, unequivocal opinions, but to have them about nearly everything, and to make those opinions publicly heard or risk accusations of ignorance or selfishness.

While I do believe human beings have responsibilities to each other, and that everyone has a right to express themselves, I have also come to believe in a right to be uncertain, to take time to make up your mind and to change it when you want to. If we appreciate indecisiveness a bit more, we can have more nuanced, honest and compassionate conversations.

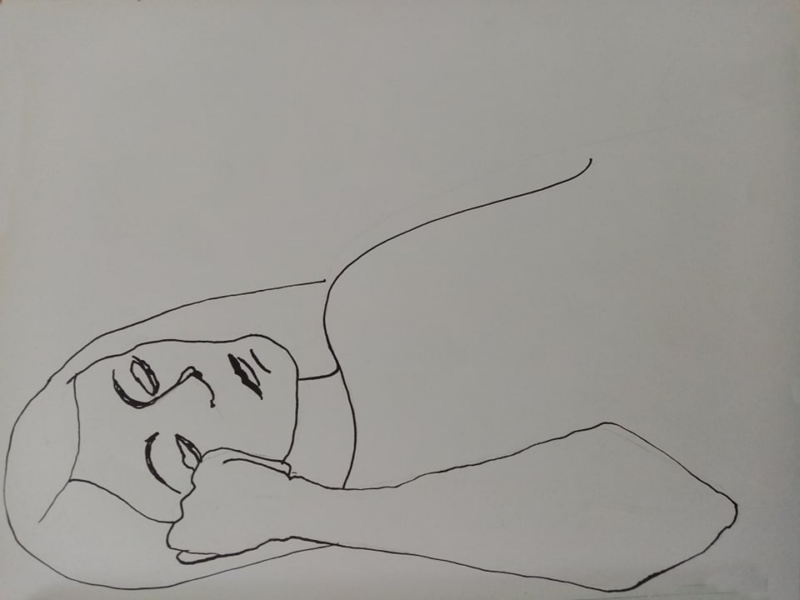

An opinionated person, I was recently arrested as I lay in bed by doubts as to how a person can make an opinion public with any confidence, especially in an era where the consensus on what is the “right” statement can shift overnight, and with very little social slack for those who got things “wrong”. I remembered all the times I have been (in my current opinion) hideously wrong in the past, and how more recent knowledge and experience have made me cringe at the misguided certainties of my teenage self.

This got me onto the possibility that my current opinions will someday seem as misguided to me as my old ones do to me now. How do I reconcile my stake in this world with the fact that there will always be infinitely more things I don’t know than there are things I know?

While I do believe human beings have responsibilities to each other, and that everyone has a right to express themselves, I have also come to believe in a right to be uncertain

My opinions have changed so much in a few years: how do I know that they won’t change as much again, and that the things I say now won’t come back to haunt me in the future? How do I know, when I speak out about something, that I am actually helping and not, in contributing to some yet-unrecognised negative trend, making things worse?

Nobody has time to properly research all the issues, about which multiple books have probably been written. Pressure to “speak out”, and a vilification of being undecided and/or silent, on whatever the latest topical issue is before you feel ready, combined with the glorification of what is “powerful” and “radical”, leads to a deluge of opinions that are underinformed and unnecessarily extreme. If you get into a situation where you are attacked for your silence on a specific topic on which you have little or no knowledge, a tempting option is to go for a quick fix: snappy, ready-made opinions, activist infographics and tweets, statements and publications from your favourite political party. Or you simply follow the general opinion of your peer group.

Nobody has time to properly research all the issues, about which multiple books have probably been written

The result is that during every major political or cultural moment, many requiring informed and sensitive treatment, we get an outpouring of (usually very similar and predictable) statements which tackle immensely complicated topics about which countless PhDs have been written with all the subtlety and grace of a rhinoceros attempting artistic gymnastics.

It is time to shed the stereotype of the apathetic, uninformed “undecideds”. My tossing and turning late at night wasn’t pleasant, but it helped remind me of the benefits of uncertainty, and its vital role in our development. Not necessarily the result of ignorance or immaturity, uncertainty can be a sign of more knowledge rather than less, indicating awareness of grey areas and willingness to admit they exist, for the more you learn about a topic’s nuances and contradictions, the harder it becomes to make bombastic, generalising statements about it without feeling dishonest and irresponsible. While uncertainty can open us up to the expertise and experience of others, too much certainty can make us more vicious and close minded towards opposing viewpoints: we assume that another person is stupid or evil because we have forgotten that their opinion may come from an experience or education that is different to our own, but no less comple: we do not allow for the fact that they might know something we don’t.

To avoid the further growth of misinformation and polarisation so connected to internet politics, we need to allow ourselves to say, “I do not know enough about this topic to have a strong opinion on it”. This is not to suggest that ignorance is something to be proud of in an anti-intellectual “that’s not worth knowing” way, but to keep us aware of our potential to learn, and to give credit where credit is due to real experts (in a university we’re usually surrounded by them) who should be listened to an awful lot more.

“I do not know enough about this topic to have a strong opinion on it” is not an expression of apathy or cowardice. It is an expression of the honesty to admit one’s own limits, of the courage to resist the pressure to oversimplify things and say things you’re not sure about just because other people expect it, of the humility to accept that we have a lot to learn and of the respect and compassion to recognise that other people have knowledge and experience that is different to our own.

“I do not know enough about this topic to have a strong opinion on it” is not an expression of apathy or cowardice. It is an expression of the honesty to admit one’s own limits

Sharing opinions is worthwhile and we all have things we feel must be talked about. I still have firm opinions on some things, this being one of them (the irony of writing in an assured “opinion mode” on the merits of not always having strong opinions is not lost on me). But I think we can benefit from telling ourselves, as my mother told me when I stressed not knowing what to think about something lately: “You don’t need to have an opinion on everything. And where you do, you can take time to make up your mind. It can take years.”

When we do make up our minds, we can be open to changing it again, and we can remember that if someone else is not of the same mind, it does not necessarily mean they are stupid or evil. (Indeed, while empathy and critical listening can help us to understand others better- considering the complexity of every individual experience, it’s generally a good policy not to assume you can completely read others’ minds, particularly the minds of those who disagree with you, which after all is a sign that their brains might travel on different trajectories to your own).

If we take the time, the patience, the courage and the humility to think carefully before we judge or speak the opinions we do eventually come out with will be more informed, more nuanced, more compassionate and, frankly, more interesting.