In a picture published in the Irish Independent in 2011, a fresh-faced Patrick Prendergast stands on the steps of the Dining Hall taking in his election victory and beaming across Front Square, blonde-haired son in his arms and his daughter hanging off his shoulder.

The picture epitomised the promise of something new that many felt amid the misery of the financial crash. Like the US electing Barack Obama, Trinity had turned to youth to clean up a mess that old men didn’t seem to have the vim and vigour to deal with.

Did his provostship live up to this heady aspiration? No, it did not. But it never could.

Should Prendergast be commended for his time in office? Yes, he should. But there are plenty of caveats.

Trinity’s provosts are often remembered for what happens in the middle of their decade in charge: John Hegarty is associated with the significant restructuring of the faculties in 2008, Tom Mitchell presided over a significant expansion of building in Trinity and Bill Watts is remembered for his preparations for Trinity’s 400th anniversary in 1992.

Trinity, Ireland and the world has changed almost beyond recognition in the past 10 years, so on this point, Prendergast is unique: his provostship cannot be easily condensed down. And for that reason, it was possibly one of the most momentous.

Crisis: ‘The Wheels Were Coming Off the Country’

Former Provost Patrick Prendergast picked arguably the worst decade since World War II to take over the top job in Trinity.

He started his time in No 1 Grafton St at the height of the financial crash, while the country was flat broke, and left office as the most destructive disease since the Spanish flu rocked the world and all but closed down the higher education sector.

His handling of these crises – while imperfect – was possibly his crowning achievement as provost. In the face of dwindling funds and a government intent on slashing public spending to curb economic woes, Prendergast got Trinity’s finances under control and kept the ship afloat, albeit in a hard-nosed fashion.

Amid a significant sectoral funding crisis, Prendergast managed to get Trinity’s finances under control

Since then, he has understandably attempted to make Trinity less dependent on a close-fisted government through philanthropy, internationalisation, allowing schools – most notably the Business School – more space to forge their own paths and, of course, commercialisation.

Commercialisation, in particular, has borne the brunt of students’ ire. The Book of Kells became a symbol of Trinity riding roughshod over students to make tourists’ lives easier.

These criticisms were often unfair, and also ignored the fact that the money coming from Trinity’s commercial ventures was going back into the university and – by extension – into student life. The Commercial Revenue Unit may sound like Trinity’s version of the Death Star, but in reality it was helping rather than hindering academia.

Prendergast also helped to open Trinity up to the outside world, encouraging international students to come to College and involving itself in initiatives like the League of European Research Universities.

Partly an attempt at raising money, this international outlook has now embedded itself in Trinity, and College has become a far more cosmopolitan place. He could, however, have done more to prepare Trinity for a post-Brexit Europe – and the painting of international students as “cash cows” has been harmful to the university.

At the end of the 2010s, he faced another challenge of biblical proportions: the coronavirus pandemic. Trinity responded quickly to it, shutting College down and moving online at a staggering pace, considering how allergic to change academics can be.

While the campus remained closed, despite massive amounts of planning by College over the summer of 2020, Prendergast appeared to want to keep Trinity at least semi-open. The libraries remained open for the most part, and coronavirus-proofed marquees – which remained empty for most of the year – were erected in New Square and Botany Bay. For much of spring and summer, students lounged in deck chairs in Library and Fellows’ Square, and could use “Buttery” slots to easily access campus.

But this is only one side of Prendergast’s approach to crises. As an engineer, he was methodical and solution-focused – and this left little room for empathy.

Prendergast often overlooked the realities on the ground in a university that has long valued collegiality.

Many schools – and junior academics and PhDs in particular – have suffered badly under austerity. All boats have not risen with the tide. The pandemic saw international students come to Ireland only to find that they had no need to be there. Many who came to Trinity Hall were miserable. Giving students 24 hours to pack up and leave their College accommodation was a lightning decision made with little thought for those who could not simply hop on a bus or plane.

While adept at standing up to immediate challenges, consultation was what really let Prendergast down, and was, in many ways, the promise that led to Provost Linda Doyle’s election in April.

Consultation: ‘So I’m sorry if it came across as dictatorial’

On the campaign trail, Doyle constantly emphasised the importance of a “re-energised democracy” in Trinity, where executive power was redistributed to the little guy.

The implication was clear: Patrick Prendergast had frozen out the rank-and-file members of the Trinity community, and Doyle promised to bring them in from the cold. That she won by telling voters that they would feel “valued and included in the decision-making of the community” is a major indictment of Prendergast’s time as provost.

Prendergast clearly found irritating anything that slowed down decision making. His no-nonsense and domineering approach to chairing College Board got him in hot water on more than one occasion.

He wanted to run things like a business, but unfortunately that often led him to overlook dissenting voices and the realities on the ground in a university that had long valued collegiality and tradition.

Outside the upper echelons of Trinity, the problem persisted. It led to a deep-rooted feeling among staff and students that College was indifferent about their plight and inaccessible.

Two iconic disasters spring to mind: the “Identity Initiative” and Take Back Trinity.

The 2013 Identity Initiative was a classically “Trinity” misstep-turned-disaster, as alumni and the campus itself went ballistic over the rebranding of the Trinity logo and name. However, it demonstrated clearly the discontent surrounding Prendergast’s tendency to overlook the College community and instead listen to highly paid advisors and branding experts.

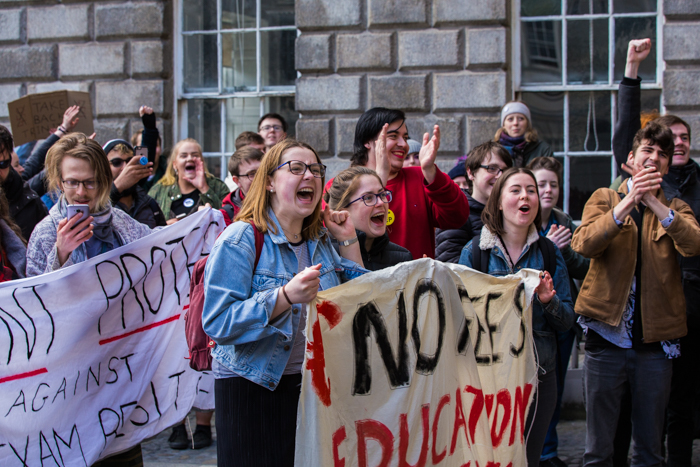

But Take Back Trinity will be one of the biggest blemishes on his legacy. College’s attempt to introduce supplemental exam fees – which triggered mass protests on campus – and its subsequent climbdown showed that Prendergast was out of touch with students but also seemingly unaware of how angry and aggrieved they felt at the time.

Take Back Trinity will be one of the biggest blemishes on Prendergast’s legacy.

Take Back Trinity will be a defining event for years to come and Trinity’s leadership was shaken by the protests. It seems unlikely now that Trinity will make such a dire decision that students would end up occupying the Dining Hall and chanting “the students, united, will never be defeated” in all out revolt against the college administration.

To his credit, Prendergast improved engagement with students after the protests, and students appeared to be higher on his list of priorities in the waning years of his time in charge.

Trinity Education – formerly known as the Trinity Education Project – however, included many of the telltale blunders and the discontent felt by the widespread curriculum changes will likely bubble under the surface for years to come.

Handling thousands of students and staff and millions of euro means that astute stewardship of the College is important, but Prendergast’s determination to run Trinity like an enterprise – and his obsession with entrepreneurship – alienated people who correctly considered the university to be just that: a university.

Money: ‘The decrease in state funding was our groundhog day’

Leaders are emergent properties: it is not just about how they do things, but the people they appoint to positions of authority, the prevailing wisdom on how best to lead and the necessities of the day.

Outside forces invariably shape what they can and cannot get done.

Money, at the end of the day, is what a university needs more than anything to thrive. And for all the talk of philanthropy and autonomy, Irish universities are heavily reliant on the government for that money.

Outside forces, such as the government of the day, invariably shape what Provosts can and cannot get done.

So, for many of the criticisms that can be levelled at the former provost, he could reasonably point to the government’s woefully inadequate support of higher education since the financial crash as an excuse.

Nowhere is this more clear than rankings. By and large, Trinity has slid down the ranks under Prendergast and College has hastened to halt the freefall. This Editorial Board has previously written that Prendergast could be remembered for rankings – and that may well be true – but the slide in rankings does not indicate decline.

In fact, on most counts, the university has improved and grown since Prendergast took over. The point is that it did not grow at the rate that other universities were able to – and money is as good an explanation for that as any.

A lot of the – very valid – frustrations that staff and students had with College could have been justifiably laid at the government’s door rather than at No 1 Grafton St.

While Prendergast ultimately failed to solve the problem of funding, there are positives to take away from his time in charge. Trinity seems to have, to some degree, shaken its posh, elitist reputation in the halls of Leinster House. Minister for Higher Education Simon Harris has in recent months frequented campus posing comfortably with Prendergast and whoever else he is there to snatch a photo with.

Prendergast can take credit for getting a miserly government to invest in his vision for Trinity.

The government has opened the door to compromise on contentious, state-enforced changes to governance structures – although Prendergast appeared initially slow to respond to these changes – and will be ploughing money into the Old Library, the E3 Learning Foundry and Trinity East.

The door is now also open for Trinity to become the pre-eminent English-speaking university in Europe, sucking in top students and academics turned off by a post-Brexit UK, and Harris appears to be on the brink of making a decision on the Cassells report and by extension the long-term financial health of the sector.

Despite at one point floating the idea of loan schemes, by the end of his tenure Prendergast had taken a strong stance on increased funding, unafraid of publicly calling the government out on its under investment. Yet little really changed over the course of the past decade from the government’s side: successive Fine Gael governments dawdled on funding and Trinity made ends meet through its own fundraising.

It is hardly a coincidence that a department of higher education was formed while Prendergast was one of the most influential people in third level. The new department could be a godsend for a sector that the government has neglected for so long.

As Doyle takes over, there is hope that the funding crisis that hounded Prendergast could be waning and it is clear that the idea of a public university funded by the government has won the day.

But if the funding crisis trundles on, Prendergast did show that Trinity can be ambitious in its capital projects, and he has helped transform campus and lay the foundations for what Trinity will look like in the future.

While those situated in the Arts Block justifiably fume about their building tearing apart at the seams, Prendergast’s changes to campus will form a major part of his legacy – perhaps most notably the Business School, which was built without state funding.

Trinity East, the new campus in the Grand Canal Docks, could be a game changer for College – Doyle banked a lot of her future plans on the development – and Prendergast can take credit for getting a miserly government to invest in his vision.

This may well be the achievement that secures a brighter future for Trinity, after the crises Prendergast grappled with for the past decade have faded into the past.