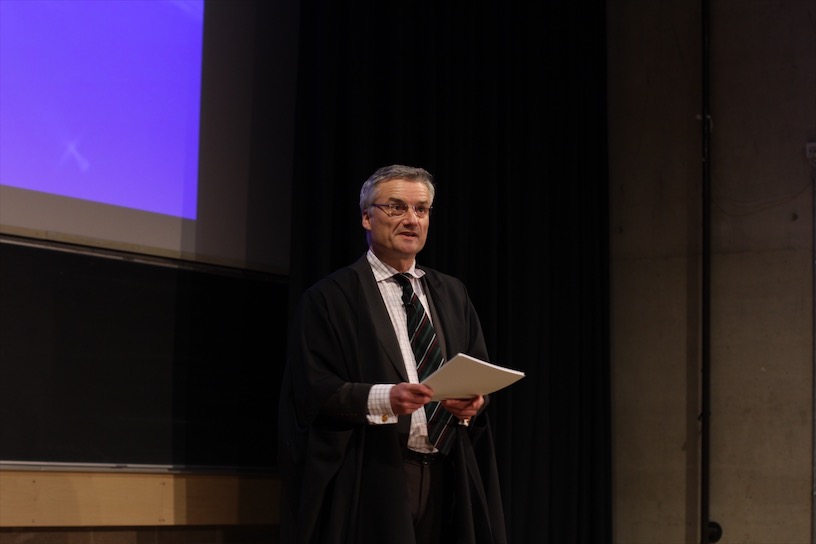

Provost Patrick Prendergast is apologetic when he emerges from House One for his final interview with The University Times as the head of Trinity: “Sorry I’m not wearing my tie.”

Prendergast’s choice of clothing is just one indicator of his winding down as he concludes his 10-year term as provost. His tone is light and self-effacing, somewhat jarring coming from a man who was, for the better part of a decade, known for his quietly intense – and, at times, domineering – posture.

But his relaxed demeanour makes sense: Prendergast is satisfied with his state of affairs at this point in time because 10 years ago he knew where he wanted to be at this point. And for the most part, reality has aligned with his expectations.

“I came in with a fairly good idea of how I wanted the 10 years to go, because I’d been Vice Provost before. So I had a fairly good idea of the way things were. I’d been the Dean of Graduate Studies before that, so I came in with a fairly good idea.”

As former President of Ireland and Trinity’s Chancellor Mary McAleese put it, Prendergast’s tenure has had “unenviable bookends” – he took up office when, as he describes it, “the wheels were coming off the country” due to recession, and he leaves as the country reels from a brutal pandemic.

I came in with a fairly good idea of how I wanted the 10 years to go

Prendergast’s successor, Prof Linda Doyle, has an unenviable task ahead of her in dealing with the fallout of the coronavirus, but Prendergast isn’t overly shaken by its effects: “Strangely enough, I managed to get most of the things that we’d planned to get done, done anyway, despite the pandemic. And actually in some respects, the pandemic accelerated some things.”

Of the Inspiring Generations campaign, he says: “When the pandemic started in March 2020, I said, ‘Crikey, we’re not going to make our €400 million target’. But in truth, fundraising didn’t slow down during the pandemic. And through Zoom and other methods, we were able to engage with people to continue fundraising.”

With the news that the Inspiring Generations campaign exceeded its goal of €400 million in donations, Prendergast’s legacy started clicking into place. The rake of capital projects that were put in the pipeline during his tenure simply could not have not have happened without philanthropy. The new home of Trinity Business School, the E3 Learning Foundry and Trinity East were all recipients of high-profile, high-sum philanthropic donations.

Another capital project that has been, it seems, nearly finished for about two years now, is Printing House Square. The new 250-bed accommodation complex was a thorn in College’s side for Prendergast’s latter years: this newspaper reported this week that the expected completion date has been pushed back yet again to September 30th.

“I would have liked to cut the ribbon on Printing House Square”, he muses. “It’s going to be lovely when it’s done. The first new square in the College in, I don’t know, maybe since Botany Bay was built … it’s great to be a Provost that built a new square.”

These two intertwined aspects of his tenure, philanthropy and capital projects, have been, on paper, a roaring success. But Prendergast’s legacy is a complex one: he was frequently criticised by students and staff alike. His detractors described him as calculating and dismissive, impatient with those who had different visions than his own.

Leadership has to step up in terms of crisis … we were going to change our financial fortunes

He falls back to the recession in defence: “The whole thing was a basket case. And it wasn’t just Trinity, it was all Irish universities and the whole public sector. So I came in, in that crisis, where we really had to get a grip on our financial situation.”

“Leadership has to step up in terms of crisis”, he says. “People may have seen that as somewhat…I think dictatorial is too strong a word, but certainly a sense of: we were on a drive, we were going to change our financial fortunes.”

He adds lightly: “So I’m sorry if it came across as dictatorial, but I think it was really focused, I suppose.”

The recession exposed the poor funding model for the higher education sector, and more than a decade on, the issue has still not been resolved. But early on, Prendergast saw opportunities to bypass the government and make money for College in other ways. And it worked: Trinity’s reliance on exchequer funding is significantly less than what it was before Prendergast took office – state funds have been replaced by philanthropy and commercial revenue. The Book of Kells is among the most popular tourist attractions in the country, College accommodation is highly sought after by summer tourists and College Park has played host to a number of lucrative gigs in recent years.

Commercialisation is a way to generate revenues and we’re generating significant revenues now through our commercial revenues. We use all the profits from those activities and we plough them back into education and research activities

But “commercialisation” quickly became a dirty word for Prendergast’s critics, particularly students. Trinity’s outward image became more steely and businesslike. Images of smiling students were sent around the world in the hopes of attracting more international applicants. College’s new business building, a towering, unfeeling structure was lauded as the “comeback story” of Irish universities, but many students weren’t convinced. The infamous Identity Initiative of 2014 – when his proposals for sweeping new College branding were widely scrutinised by staff and mocked by students – was, arguably, the ultimate lesson in how not to attempt to alter public image.

Prendergast doesn’t deny that College is now run like a business: “You know, universities should be businesslike and should be run efficiently and effectively. Commercialisation is a way to generate revenues and we’re generating significant revenues now through our commercial revenues. We use all the profits from those activities and we plough them back into education and research activities.”

So does he dispute the common accusation that College cares more for tourists than it does students?

“It’s completely wrong. We don’t care more about tourists than we do about students”, he says curtly. “The whole college is set up primarily for students: teaching students and to the benefit of the student experience. But I would say that those that come in who are tourists and visitors do deserve to have some consideration given to their experience as well and it’s a balance between the two.”

But he also admits that such accusations are not entirely unfounded. “In the last year before the pandemic, I did worry a little bit that there were too many tourists on campus. I live [in] the College. So I walk out to Front Square on Saturday morning and the place is full, like some Italian piazza [and] I’m thinking: maybe this is not good, because students are living in College.”

The whole college is set up primarily for students: teaching students and to the benefit of the student experience. But I would say that those that come in who are tourists and visitors do deserve to have some consideration given to their experience

“My own daughters, who are both students here, would tell me that, you know, you’d be queuing for coffee in the Arts Block and it’s not students that are queuing up – it’s tourists.”

“Now of course, we want to provide for the tourists that come into the College. But really, the Arts Block should be primarily a place for students to congregate, meet, talk, discuss.”

So what spurred this – partial – change of heart about tourism? It’s hard not to assume it was Take Back Trinity. On the back of an announcement of new €450 fees for supplemental exams, enraged students decided that they had had enough, occupying the Dining Hall and making their disapproval of commercialisation quite clear.

Take Back Trinity was, Prendergast says, “the students questioning the rationale behind the commercial activities”.

When you lose the ability to keep a dialogue going, then nobody benefits from that

“If you end up doing so many commercial activities [that] are beginning to deteriorate the student experience, then, of course, it’s a self-defeating cycle. And we want to make sure not to get into that, we really do not want to get into that.”

So were the protests a turning point?

He pauses. “At that stage we’d lost the ability to keep a dialogue going between College leadership and the students. And whenever that happens, when you lose the ability to keep a dialogue going, then nobody benefits from that.”

Lack of communication between College’s upper echelons and those with boots on the ground was a regular talking point during the provost elections. Prendergast’s own manifesto in 2011 pledged to “make staff morale one of [his] priorities”. But, as this newspaper reported, many felt this was largely unsuccessful. The Provost had his allies, but many of those further away from him felt frustrated by his arm’s-length approach.

But Prendergast believes this a perennial issue. “When I came here to work under Provost Mitchell, [he] was always talking about staff morale being low … And I remember I worked with John Hegarty, my predecessor and his administration and they had many meetings where staff morale was ‘never lower’.”

There’s more of a compliance and oversight culture [in] public-sector organisations. And maybe that’s right, because we’re spending a large part of taxpayers’ money

Despite his reputation, Prendergast is remarkably composed in public. But the staff morale issue prompts a hint of frustration. “What do you do to make people happy?”

The bureaucracy, he says, stems from the need to remain transparent: “There’s more of a compliance and oversight culture [in] public-sector organisations. And maybe that’s right, because we’re spending a large part of taxpayers’ money. So we should be accountable. And this accountability does create, unfortunately, more bureaucracy for us all.”

“[Staff are] working in a great university, [with] committed students, by and large, [who] want to learn. The financial situation is sound, so we haven’t had to commence salary cuts, we’ve been able to do promotions, maybe not as many as people want, but still pretty good, same as in previous decades. We’ve dug ourselves out of the financial hole that we had in 2011.”

As his provostship draws to a close, Prendergast is “relieved”: “10 years is a long time. And I’ve enjoyed it, enjoyed every minute of it.”

He politely declines to give advice to his successor. “People have asked me that before and I [won’t] give Linda Doyle advice because she knows exactly her own mind. I purposely don’t have advice … my advice, if there’s any advice, is to know your own mind. But I know she knows her own mind anyway.”

Though he claims that he looked forward to every meeting in the past decade, “it’s come to the time now to move on and do new things”. One new thing is a research professorship, the traditional course of action for a finishing provost who isn’t retiring. However, instead of returning to his old field of study, bioengineering and medical devices, Prendergast will be examining “the great challenge of our time, which is the climate crisis”.

“I’d like to begin thinking more about the problems that arise as humanity reconciles itself with the fact that it has to change how it uses this planet if it’s going to flourish on in the future.”

This sounds rather taxing for someone just off the back of a decade of running an entire university. But he won’t be jumping immediately into his new position. “I’m going to do nothing, only read novels for the next six months.”